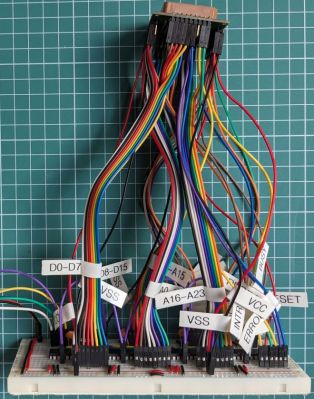

[Yeckel] recently put the finishing touches on an ambitious implementation of a simple D-STAR (Digital Smart Technologies for Amateur Radio) transceiver using some very accessible and affordable hardware. The project is D-StarBeacon, and [Yeckel] shows it working on a LilyGO TTGO T-Beam, an ESP32-based development board that includes a SX1278 radio module and GPS receiver. It even serves a web interface for easy configuration.

What is D-STAR? It’s a protocol used by radio operators for voice that also allows transmitting low-speed data, such as short text messages or GPS coordinates. While voice is out of scope for [Yeckel]’s project (more on that in a moment) it can do all the rest, including send images. That makes beacon-type functions possible on inexpensive hardware, instead of requiring a full-blown radio.

As mentioned, voice is a big part of D-STAR. While [Yeckel] was able to access the voice data, attempts to decode it were unsuccessful. A valiant effort, but we suppose voice decoding isn’t terribly relevant to beacon-type operations like transmitting APRS (Automatic Packet Reporting System).

So far as [Yeckel] is aware, D-StarBeacon is currently the only open-source implementation of a D-STAR radio available on the internet, which is pretty interesting. We’ve seen projects that touch indirectly on D-STAR, but nothing like this.

Watch it go through its paces in the video embedded below. Since the T-Beam is just a microcontroller development board, the user interface comes from an Android app on a mobile phone, which is why you see a phone in the video.

Continue reading “Simple D-STAR Transceiver Uses Inexpensive Hardware” →