The MAX30105 is an optical sensor capable of a great many things. It can sense particulate matter in the air, or pick up the blinking of an eye. Or, you can use it as a rudimentary way to measure your heart rate and blood oxygen levels. It’s by no means a medical grade tool, but this build from [Taste The Code] is still quite impressive.

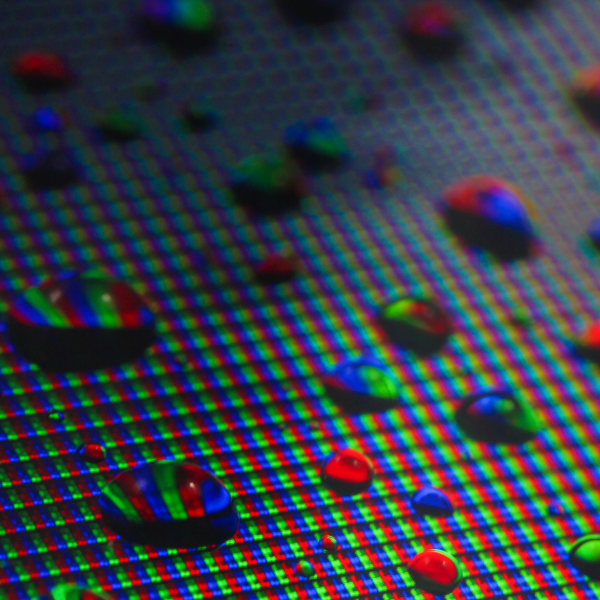

The MAX30105 contains red, green, and infrared LEDs, and a very sensitive light detector. The way it works is by turning on its different LEDs, and then carefully measuring what gets reflected back. In this way it can measure particles in the air, such as smoke, which is actually what it was designed for originally. Or, if you press your finger up against it, it can measure the light coming back from your blood and determine its oxygenation level. By detecting the variation in the light over time, it’s possible to pick up your pulse, too.

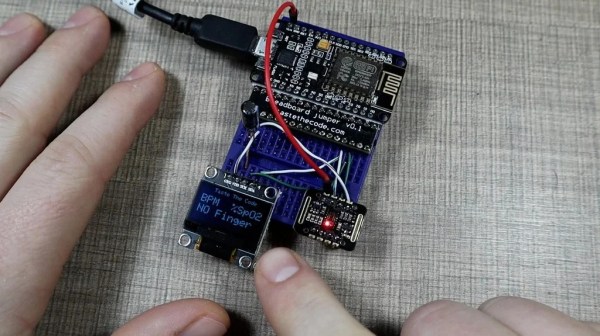

Getting this data out of the sensor is remarkably easy. One need only hook it up to a suitable microcontroller like the ESP8266 and use the MAX3010X library to talk to it. [Taste The Code] did exactly that, and also hooked up a screen for displaying the captured data. Alternatively, if you want the raw data from the sensor, you can get that too.

It should be noted that this build was done for educational purposes only. You shouldn’t rely on a simple DIY device for gathering useful medical data; there are reasons the real gear is so expensive, after all. We’ve looked at this sensor before, too, not long after it first hit the market. Continue reading “This Air Particulate Sensor Can Also Check Your Pulse Rate”