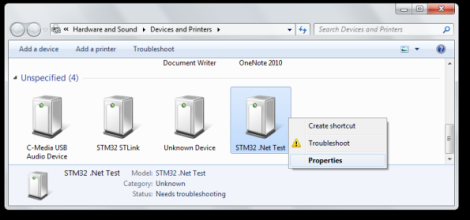

The USB device seen plugged in on the right of this image was found in between the keyboard and USB port of the company computer belonging to a Senior Executive. [Brad Antoniewicz] was hired by the company to figure out what it is and what kind of damage it may have done. He ended up brute forcing an unlock code to access the device, but not before taking some careful steps along the way.

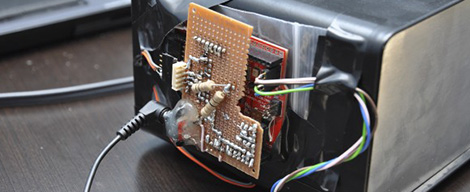

From the design and placement the hardware was most likely a key logger and after some searching around the Internet [Brad] and his colleagues ordered what they thought was the same model of device. They wanted one to test with before taking on the actual target. The logger doesn’t enumerate when plugged in. Instead it acts as a pass-through, keeping track of the keystrokes but also listening for a three-key unlock code. [Brad] wrote a program for the Teensy microcontroller which would brute force all of the combinations. It’s a good thing he did, because one of the combinations is a device erase code hardwired by the manufacturer. After altering the program to avoid that wipe code he successfully unlocked the malicious device. An explanation of the process is found in the video after the break.

Continue reading “Brute Force Used To Crack A Key Logger’s Security Code”