[Brendan Sleight] has been hard at work on this wearable piece of tech. He doesn’t wear much jewelry, but a wedding ring and some cufflinks are part of his look. To add some geek he designed a set of cufflinks that function like traffic lights. Since he still had some program space left he also rolled in extra features to compliment the traffic light display.

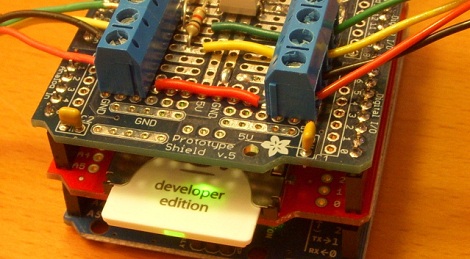

That link goes to his working prototype post, but you’ll want to look around a bit as his posts are peppered with info from every part of the development process. The coin-sized PCB hiding inside the case plays host to a red, amber, and green surface mount LED. To either side of them you’ll find an ATtiny45 and a RV-8564-C2. The latter is a surface mount RTC with integrated crystal oscillator, perfect for a project where space is very tight.

The design uses the case as a touch sensor. Every few seconds the ATtiny wakes up to see if the link is being touched. This ensures that the coin cell isn’t drained by constantly driving the LEDs. The touch-based menu system lets you run the links like a stop light, or display the time, date, or current temperature. See a quick demo clip after the break.