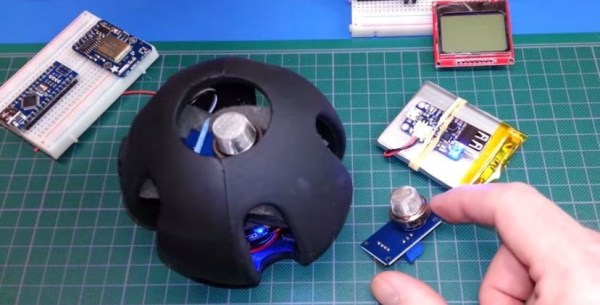

Ever consider monitoring the air quality of your home? With the cost of sensors coming way down, it’s becoming easier and easier to build devices to monitor pretty much anything and everything. [AirBoxLab] just released open-source designs of an all-in-one indoor air quality monitor, and it looks pretty fantastic.

Capable of monitoring Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs), basic particulate matter, carbon dioxide, temperature and humidity, it takes care of the basic metrics to measure the air quality of a room.

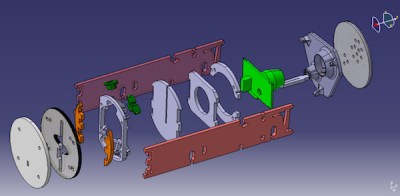

All of the files you’ll need are shared freely on their GitHub, including their CAD — but what’s really awesome is reading back through their blog on the design and manufacturing process as they took this from an idea to a full fledged open-source device.

Did we mention you can add your own sensors quite easily? Extra ports for both I2C and analog sensors are available, making it a rather attractive expandable home sensor hub.

To keep the costs down on their kits, [AirBoxLab] relied heavily on laser cutting as a form of rapid manufacturing without the need for expensive tooling. The team also used some 3D printed parts. Looking at the finished device, we have to say, we’re impressed. It would look at home next to a Nest or Amazon Echo. Alternatively if you want to mess around with individual sensors and a Raspberry Pi by yourself, you could always make one of these instead.

The Hardware in Satellite receivers is running Linux. They use a card reader to pull in a Code Word (CW) which decodes the signal coming in through the satellite radio.

The Hardware in Satellite receivers is running Linux. They use a card reader to pull in a Code Word (CW) which decodes the signal coming in through the satellite radio.