Depending upon where you live in the world, the chances are that your national or local government, or your utility company, has smart meters on their agenda. The idea is that these network-connected energy meters for your gas and electricity supply will allow greater control of energy usage and lead to lower costs through more efficient use of that energy. Bold plans have been advanced for meters that exert control over your higher-power appliances such as water heaters, washing machines, or home heating systems, able to turn them off or on depending on the time of day, spot price of energy, or load on the grid as a whole.

These devices are not without controversy though. Privacy concerns for example, centred on the amount of information about individuals that could be gleaned from the data they collect. Or security, that a vulnerability in an internet-connected electronic device fitted to millions of homes and with control over high-power appliances could be catastrophic if successfully exploited.

In a small area of Paris, they are trying to reap some of the benefits of smart meters for a community without some of those risks. CitizenWatt (French language, Google Translate link) is an open-source smart energy monitor that provides some of the benefits of a smart meter while allowing its owner to retain control of the data it generates by sharing data only with their consent. The entire project was born of an association between Citoyens Capteurs (Citizen Sensors, French language, Google Translate link), the hackEns (French language, Google Translate link) hackspace, the Fabelier FabLab, and the City of Paris.

The CitizenWatt system comprises an electricity sensor and a base station. The sensor is a simple battery-powered device that takes the output from a current transformer clamped onto the electricity supply cable and feeds it via an ATMEGA8 microcontroller to a 2.4GHz RF link. The base station is a Raspberry Pi which retrieves the data from the RF, stores it, and allows the user to view it through a web interface. Both the sensor code and hardware files, and the files for the Raspberry Pi base station are freely available on GitHub.

In keeping with the open nature on their project, the CitizenWatt team organised a series of events at which the families who were part of their trial in a Paris suburb were given the chance to build their own sensor boards, for many of them the first time they had handled a soldering iron.

We have seen quite a few smart meters on these pages over the years. There is this one based on a Spark Core, this one based on an ESP8266, and this one provided by a utility company, the data of which can be accessed. CitizenWatt is a worthy project to join them in its own right, but its involvement of a local community of non-makers is what sets it apart. We applad this aspect of the project, and we wish we saw more like it.

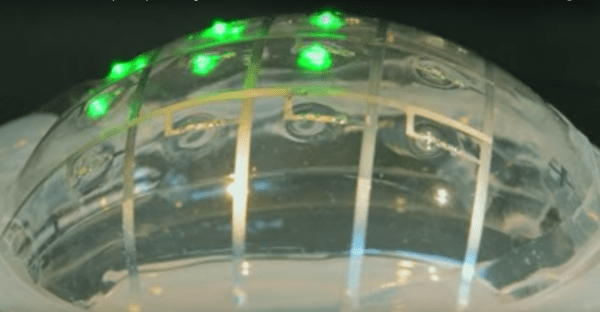

Researchers at the

Researchers at the