Introduced last year as an improvement on the very popular Shapeoko CNC router, the X-Carve by Inventables has grown to be a very well-respected machine in the community. It’s even better if you throw a DeWalt spindle on there, allowing you to cut almost everything that’s not steel. With a recent upgrade to the X-Carve, it’s even more capable, featuring the best mods and suggestions from the community that has grown up around this machine.

The newest iteration of the X-Carve features higher power drivers, better rigidity, and a heat sink for the spindle. That last item is an interesting bit of kit – routing takes time, and a 1¼HP motor will turn electricity into heat very effectively.

In addition to the 500mm square and 1000mmm square routers previously available, there’s a new, 750mm square machine available. All machines feature a new electronics box for the X-Carve, the X-Controller. This ‘brain box’ is a combined power supply, stepper driver, and motion controller built into a single box. The stepper drivers are able to supply 4A to a motor, is capable of 1/16 microstepping, and has connections for limit switches, spindle control speed, a Z probe, and outputs for vacuums or coolant systems. The underlying controller is based on grbl, making this brain box a very solid foundation for any 3-axis CNC build. The ‘brain box’ format seems to be the way the hobbyist CNC market is going, considering the whispers and rumors concerning Lulzbot selling their Taz6 brainbox independently from a 3D printer.

In addition to the 500mm square and 1000mmm square routers previously available, there’s a new, 750mm square machine available. All machines feature a new electronics box for the X-Carve, the X-Controller. This ‘brain box’ is a combined power supply, stepper driver, and motion controller built into a single box. The stepper drivers are able to supply 4A to a motor, is capable of 1/16 microstepping, and has connections for limit switches, spindle control speed, a Z probe, and outputs for vacuums or coolant systems. The underlying controller is based on grbl, making this brain box a very solid foundation for any 3-axis CNC build. The ‘brain box’ format seems to be the way the hobbyist CNC market is going, considering the whispers and rumors concerning Lulzbot selling their Taz6 brainbox independently from a 3D printer.

The new X-Carve is available now, with a fully-loaded 1000mm wide machine coming in at about $1400. That’s comparable to many other machines with the same volume, unlike the Chinese 3040 CNC machines, you don’t need to find an old laptop with a parallel port.

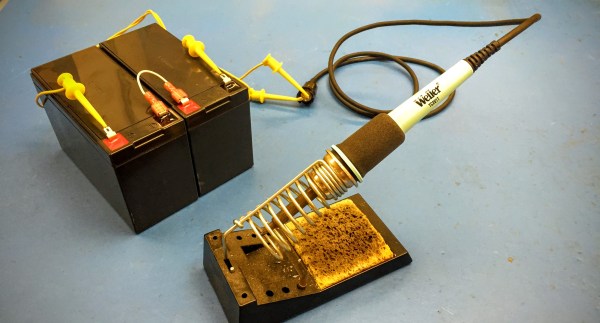

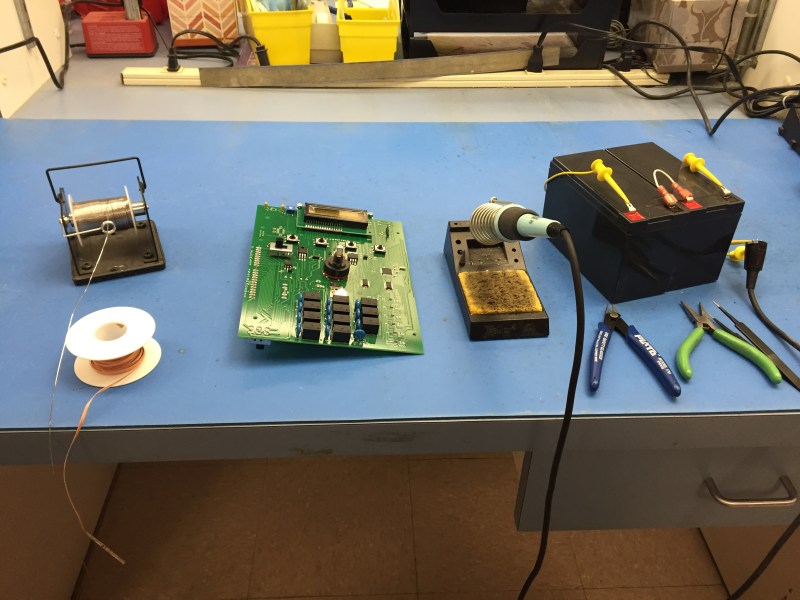

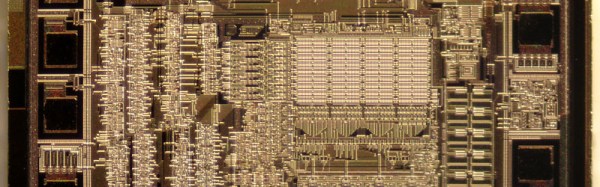

[whitequark] has been experimenting with a blowtorch for SMD reflow. Having just moved 8,000 km [whitequark] was stuck without any of the usual reflow tools. They did however have a blowtorch handy, and gave it a go.

[whitequark] has been experimenting with a blowtorch for SMD reflow. Having just moved 8,000 km [whitequark] was stuck without any of the usual reflow tools. They did however have a blowtorch handy, and gave it a go.