Venture away from your workbench and see what others have been building this year. It’s time for Hackaday World Create Day when hackers all over the world get together to work on projects.

On April 22nd, join the creative minds in your area for a few hours of build time. It’s an opportunity to inspire and be inspired by others. There’s no better way to make those leaps forward on a project than to share your work with others. This pollination of ideas is what sparks creativity, and it’s a great excuse to meet new people.

Find a meetup near you right now. Don’t see one in your area? Become a host, it’s easy and we’ll help!

What’s It Like at a World Create Day Meetup?

When the Hackaday community gets together it’s always a fun time. Each meetup on April 22nd will be unique. These are organized locally and given life by those who show up. Bring an open mind and something you’re excited about and you’ll be right at home.

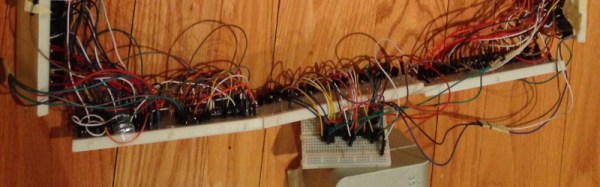

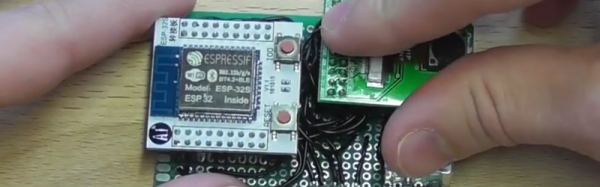

For instance, if I were Brian Benchoff I might bring along my 3D printed WiFi antenna and a few different WiFi devices to see if anyone wanted to do some distance measurements and signal strength characterization. I myself have been working on an art project that uses computer vision and replacement display for my exercise machine so I’ll bring one of those. After a few hours of hacking, it’s customary to go around the room and have people give a very brief explanation of their work.

World Create Day is the perfect place to put together you Hackaday Prize Team. As the ideas fly, keep in mind the power of one idea to change the world. Consider picking a challenge, brainstorming an idea, and entering it in the Hackaday Prize.

Pics or It Didn’t Happen

Don’t let the great ideas live for only one day. Make sure you tell the story of your World Create Day. Post your pictures and descriptions on social media with hashtag #WorldCreateDay during the event. Pictures, project links, and a brief summary should be added on your meetup’s Hackaday.io event page. We want to cover as many of these as possible on Hackaday, so don’t be bashful about telling everyone what people at your meetup were working on — finished project or pencil drawing, we want to hear it!