Those beautiful and dangerous ocean waves that beckon us to the coast are more than just a pretty sight. They can tell us a lot about weather patterns and what the sea itself is doing. As vital as this information is, the existing methods of doing wave research are pretty expensive. The team at [t3chflicks] wanted to show it can be done fairly cheaply, to encourage more citizen scientists to contribute. More data means a better understanding, and open research benefits even those who don’t actively participate.

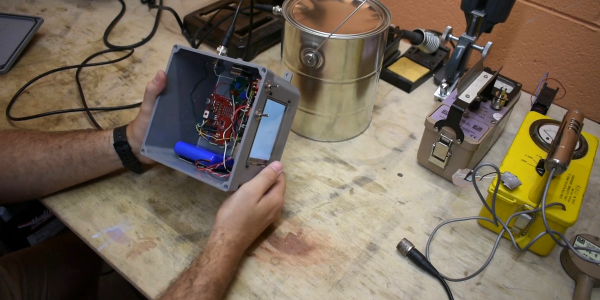

They have developed a smart buoy that collects wave data and transmits it back to a base station for real-time display. The buoy runs on an 18650 that gets recharged by four 5V solar panels situated around the top half of the 3D-printed hull. An Arduino inside the buoy controls the sensors, most of which are baked into the GY-86 10-DOF module. The antenna on top sends the data back to a Raspi Zero base station, which charts wave height, wave period, wave power, water and air temperature, and barometric pressure in real-time on a spiffy Vue JS dashboard.

The team had their ups and downs during this project. They wanted to measure wave direction, but it proved a bit too complicated. And memory issues prevented them from backing up the data to an on-buoy SD card. You can catch the more in-depth hardware and software videos on their YouTube channel. We’ve got the smart buoy summary video tied up and floating just after the break.

Want to help buoy wave research, but don’t have a 3D printer? Sealed PVC makes a fine flotation device, as we saw in this water quality-sensing buoy.

Continue reading “Smart Buoy Rides The Citizen Science Wave”

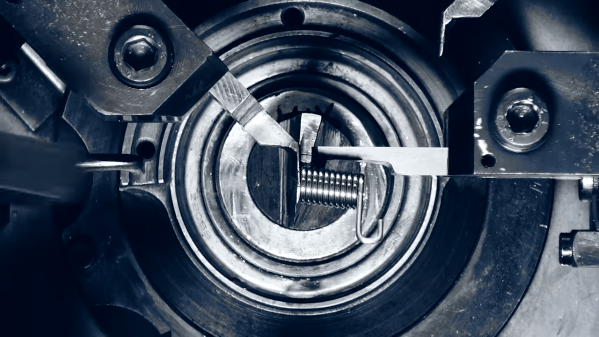

While this promise might seem abstract, consider the movements made by a 3D printer. Many styles of this machine rely on motor-driven movement along three orthogonal axes: X, Y, and Z. We usually restrict individual motor movement to a single axis by constraining it using a precision part, like a linear rod or rail. However, the details of how we physically constrain the motor’s movements using these parts is a non-trivial task. Overconstrain the axis, and it will either bind or wiggle. Underconstrain it, and it may translate or twist in unwanted directions. Properly constraining a machine’s degrees of freedom is a fundamental aspect of building a solid machine. This is the core subject of the book: how to join these precision parts together in a way that leads to precision movement only in the directions that we want them.

While this promise might seem abstract, consider the movements made by a 3D printer. Many styles of this machine rely on motor-driven movement along three orthogonal axes: X, Y, and Z. We usually restrict individual motor movement to a single axis by constraining it using a precision part, like a linear rod or rail. However, the details of how we physically constrain the motor’s movements using these parts is a non-trivial task. Overconstrain the axis, and it will either bind or wiggle. Underconstrain it, and it may translate or twist in unwanted directions. Properly constraining a machine’s degrees of freedom is a fundamental aspect of building a solid machine. This is the core subject of the book: how to join these precision parts together in a way that leads to precision movement only in the directions that we want them.