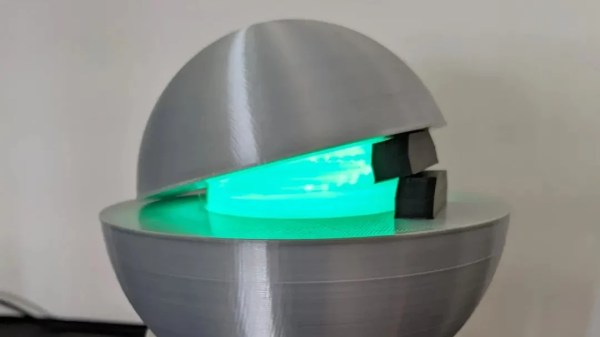

While on the search for an alternative to directly buying the fairly expensive MH-Z19 CO2 sensor, [spezifisch] came across a ‘BreeRainz’ branded gadget (also found under other brands) that claimed to use an NDIR (Non-Dispersive Infrared) sensor for measuring CO2 levels, while costing only €25. This type of sensor allows for CO2 levels to be measured directly, rather than inferred, making them significantly more precise.

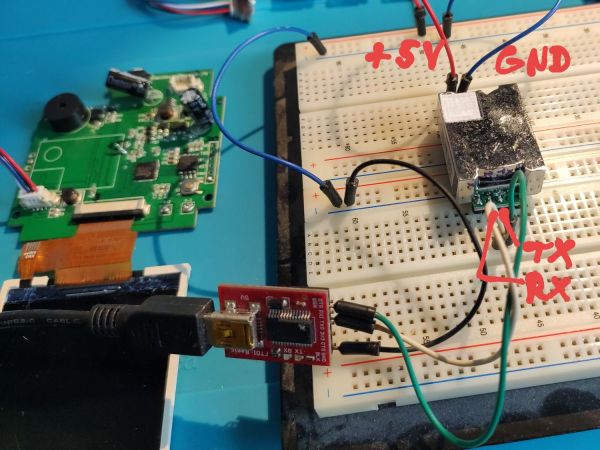

After cracking the gadget open (literally, due to the hidden screws), the CO2 sensor is clearly visible. While superficially identical to an MH-Z19, the NDIR sensor is actually called ‘HC8’, is produced by 广州海谷电子科技有限公司 (Guangzhou Haigu Electronic Technology Co., Ltd.). While being pin-compatible with the MH-Z19, its UART protocol is not the same. Fortunately there is a datasheet to help with implementing it, which is what [spezifisch] did.

This raises the question of whether harvesting NDIR CO2 sensors like this is worth it to save a few Euros. A quick look on German Amazon shows that the device in question currently costs €35, while a genuine MH-Z19 can be bought for €25 or less. There are also many MH-Z19 models (B, C and D), which cover an even wider price range. All of which points to finding an NDIR sensor-containing device can be interesting when it’s on sale, but if all you care about is the sensor itself, it’s probably best to just buy them directly.