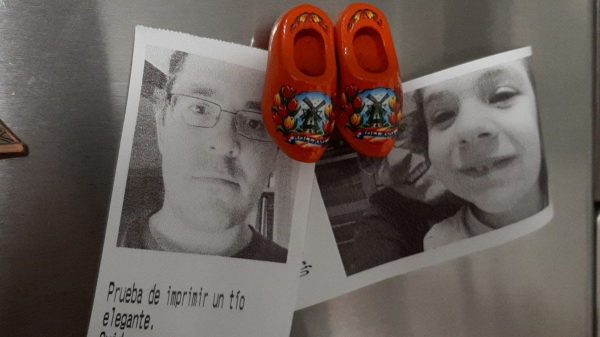

A discussion ensued about our crazy hacker ways the other night. I jokingly suggested that with as many stickers as we each had on our trusty companion machines, they might literally be as unique as a fingerprint. Cut straight to nerds talking too much math.

First off, you could wonder about the chances of two random hackers having the same sticker on their laptop. Say, for argument’s sake, that globally there are 2,000 stickers per year that are cool enough to put on a laptop. (None of us will see them all.) If a laptop lasts five years, that’s a pool of 10,000 stickers to draw from. If you’ve only got one sticker per laptop, that’s pretty slim odds, even when the laptops are of the same vintage.

Real hackers have 20-50 stickers per laptop — at least in our sample of “real hackers”. Here, the Birthday Paradox kicks in and helps us out. Each additional sticker provides another shot at matching, and an extra shot at being matched. So while you and I are unlikely to have the same birthday, in a room full of 42 people, it’s 90% likely that someone will have their birthday matched. With eight of us in the room, that’s 240 stickers that could match each other. (9999 / 10000) ^ (240 * 210 / 2) = about an eight percent chance of no match, so a better than 90% chance that we’d have at least one matching sticker.

But that doesn’t answer the original question: are our be-stickered laptops unique, like fingerprints or snowflakes? There, you have to match each and every sticker on the laptop — a virtually impossible task, and while there were eight of us in the room, that’s just not enough to get any real juice from the Birthday Paradox. (1/10,000) ^ 30 = something with -120 in the exponent. More than all the atoms in the universe, much less hackers in a room, whether you take things to the eighth power or not.

I hear you mumbling “network effects”. We’ve all gone to the same conferences, and we have similar taste in stickers, and maybe we even trade with each other. Think six degrees of separation type stuff. Indeed, this was true in our room. A few of us had the same stickers because we gave them to each other. We had a lot more matches than you’d expect, even though we were all unique.

So while the math for these network effects is over my head, I think it says something deeper about our trusty boxen, their stickers, and their hackers. Each sticker also comes with a memory, and our collected memories make us unique like our laptops. But matching stickers are also more than pure Birthday Paradoxes, they represent the shared history of friends.

Wear your laptop stickers with pride!