Among us Hackaday writers, there are quite a few enthusiasts for retro artifacts – and it gets even better when they’re combined in an unusual way. So, when we get a tip about a build like this by [Sam Christy], our hands sure start itching.

The story of this texting typewriter is one that beautifully blends nostalgia and modern technology. [Sam], an engineering teacher, transformed a Panasonic T36 typewriter into a device that can receive SMS messages, print them out, and even display the sender’s name and timestamp. For enthusiasts of retro gadgets, this creation bridges the gap between analog charm and digital convenience.

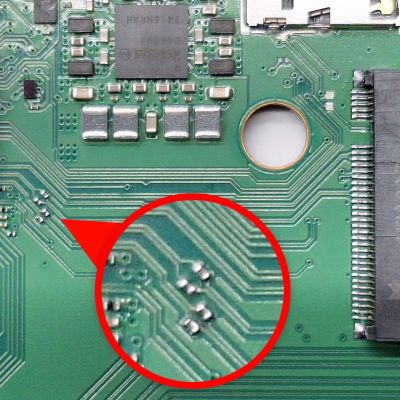

What makes [Sam]’s hack particularly exciting is its adaptability. By effectively replacing the original keyboard with an ESP32 microcontroller, he designed the setup to work with almost any electric typewriter. The project involves I2C communication, multiplexer circuits, and SMS management via Twilio. The paper feed uses an “infinite” roll of typing paper—something [Sam] humorously notes as outlasting magnetic tape for storage longevity.

Beyond receiving messages, [Sam] is working on features like replying to texts directly from the typewriter. For those still familiar with the art form of typing on a typewriter: how would you elegantly combine these old machines with modern technology? While you’re thinking, don’t overlook part two, which gives a deeper insight in the software behind this marvel!

Continue reading “Back To The Future Of Texting: SMS On A Panasonic Typewriter”