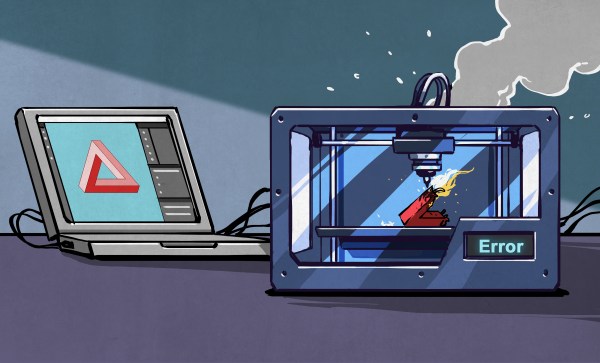

A few months ago, Hackaday’s own Al Williams convinced me to buy a couple of untested, returned-to-manufacturer 3D printers. Or rather, he convinced me to buy one, and the incredible success of the first printer spurred me on to the second. TL;DR: Lightning didn’t strike twice, but I’d still rate it as worth my time. This probably isn’t a good choice for your first printer, but if you’ve done the regular maintenance on your first printer already, I’d recommend it for your second or twelfth.

As background, Al has been volunteering with local schools to teach a 3D printing summer class, and this means outfitting them with a 3DP lab on the dirt cheap. His secret is to buy last year’s model which has all of the features he needs – most importantly for the kids, automatic bed height probing – but to buy it from the scratch-and-dent shelf at Creality. Why? Because they are mid-grade printers, relatively new, but on deep discount.

How deep? I found an essentially endless supply of printers that retail for $300 on discount for $90 each. The catch? It might work, it might not. I bought my son one, because I thought that it would at least make a good project for us to work on together. Those plans were spoiled – it worked absolutely flawlessly from the moment we bolted it together, and he runs 24-hour jobs on the thing without fear. From the look of the build plate, it had been used exactly once and returned for whatever reason. Maybe the owner just didn’t want a 3D printer?

The siren song of straightforward success was too much for me to resist, and I picked another up to replace my aging A8 which was basically a kit for a 3D printer, and not a particularly good one at that, but could be made to work. My scratch-and-dent Creality came with a defective bed-touch sensor, which manifest itself as a random absolute refusal to print.

I took it apart, but the flaw is in the design of the V1 touch sensors – the solenoid requires more current to push down than the 3DP motherboard can reliably deliver. It works 100% of the time on my bench power supply, but in situ it fails about 30% of the time, even after hitting it with graphite and making sure everything is mechanically sound. Creality knows this and offers a free trade-in, just not for me. The new version of the Creality probe costs $50 new, but you can get cheap knock-off BL Touch models for $14. Guess what I did?

And guess what bit me? The cheapo touch probe descends a bit slower than the Creality version should, and the firmware is coded to time-out in an extra-short timeframe. Thankfully, Creality’s modifications to Marlin are all open source, and I managed to tweak and flash a new firmware that made it work 100% of the time, but this was at a cost of probably eight hours of bug-hunting, part-ordering, and firmware-compiling. That said, I got some nice extra features along the way, which is the advantage of a printer running open-source firmware.

So my $300 printer cost me $105, plus eight hours of labor. I only charge one coffee per hour for fun hardware debugging tasks, but you may have a different valuation. Taken together with my son’s printer, we have $600 worth of printer for under $200 plus labor, though, which starts to sound a little better.

Is gambling on an untested return 3D printer worth it? For us, I would say it was, and I’d do it again in a few years. For now, though, we’ve got three printers running and that’s all we need. Have you gone down this perilous path?