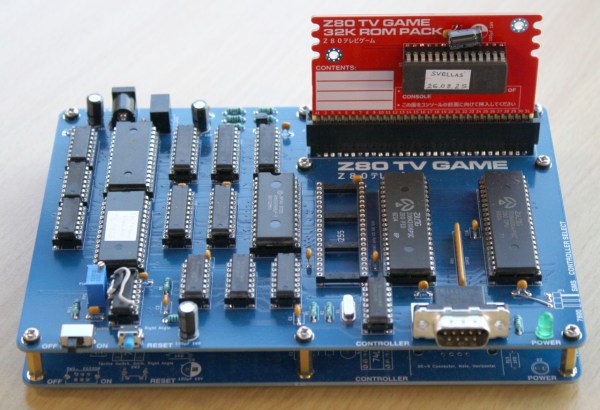

There are still a few days before the doors open on this year’s Hackaday Supercon in Pasadena, but for the most dedicated attendees, the badge hacking has already begun…even if they don’t have a badge yet.

By referencing the design files we’ve published for this year’s Communicator badge, [Thomas Flummer] was able to produce this gorgeous 3D printed case that should be immediately recognizable to fans of the original Star Trek TV series.

Although the layout of this year’s badge is about as far from the slim outline of the iconic flip-up Trek communicator as you can get, [Thomas] managed to perfectly capture its overall style. By using the “Fuzzy Skin” setting in the slicer, he was even able to replicate the leather-like texture seen on the original prop.

Between that and the “chrome” trim, the finished product really nails everything Jadzia Dax loved about classic 23rd century designs. It’s not hard to imagine this could be some companion device to the original communicator that we just never got to see on screen.

While there’s no denying that the print quality on the antenna lid is exceptional, we’d really like to see that part replaced with an actual piece of brass mesh at some point. Luckily, [Thomas] has connected it to the body of the communicator with a removable metal hinge pin, so it should be easy enough to swap it out.

Considering the incredible panel of Star Trek artists that have been assembled for the Supercon 2025 keynote, we imagine this won’t be the last bit of Trek-themed hacking that we see this weekend — which is fine by us.