In recent years, Cosplay as a hobby has seen improvement in the props department by leaps and bounds. Thanks in part due to the rise of the Maker culture and the easy availability of design and manufacturing tools and processes. Case in point is this awesome set of Animatronic Wings that programmer [Nelson Stoldt] built for his daughter who wanted to be Nightmare Moon.

[Nelson] had no idea what he’d gotten himself in to when he answered “Sure, I can do that”. Making motorized cosplay wings that open up to 8 feet wide and close again at the flick of a switch without weighing a ton is not a trivial project. The final rig did end up tipping the scales at just over 9 kgs, but we guess that’s a load that Cosplayers are used to hauling around.

Using a nifty program called Linkage, he played around with a few different design approaches until he found a mechanism that worked well. If you ever want to build one of [Theo Jansen]’s Strandbeest, give this program a spin. Armed with this information, and a spreadsheet to help determine the exact length of each linkage element, he modelled the project in Sketchup. The wings are operated by a scissor mechanism that is driven by a motorized screw operated sliding carriage. Wing position is measured by a potentiometer coupled to one of the wing elements. Basically, he just built a huge, powerful servo.

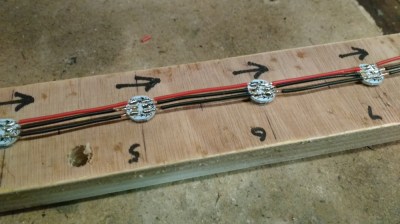

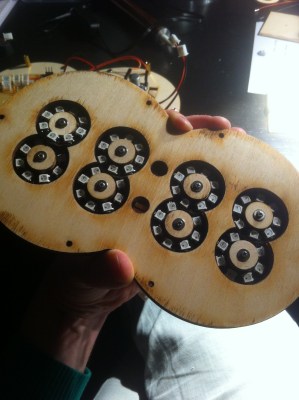

For starters, he got panels (as in PCB panels) of WS2812 boards from eBay. The advantage is it lets you choose your own pitch and strand length. The flip side is, you need to de-panel each board, mount it in a jig, and then solder three lengths of hook up wire to each LED. He planned for an eight sided star with ten LED’s each. And he built three of them. So the wiring was, substantial, to say the least. And he had to deal with silicone sealant that refused to cure and harden. But nothing that some grit and determination couldn’t fix.

For starters, he got panels (as in PCB panels) of WS2812 boards from eBay. The advantage is it lets you choose your own pitch and strand length. The flip side is, you need to de-panel each board, mount it in a jig, and then solder three lengths of hook up wire to each LED. He planned for an eight sided star with ten LED’s each. And he built three of them. So the wiring was, substantial, to say the least. And he had to deal with silicone sealant that refused to cure and harden. But nothing that some grit and determination couldn’t fix.

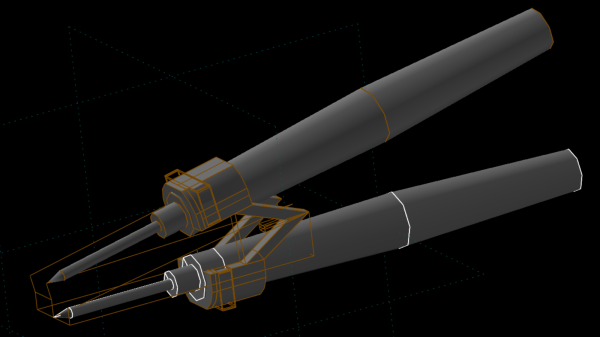

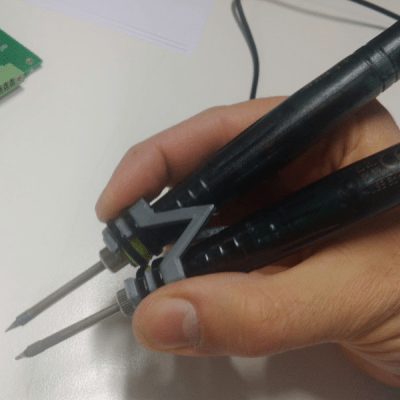

[adria.junyent-ferre] took a pair of cheap £5 USB soldering irons and turned them into a nifty pair of

[adria.junyent-ferre] took a pair of cheap £5 USB soldering irons and turned them into a nifty pair of

Each digit is made using one pair of Neopixel rings, stacked to form a figure of eight. All the digits are composed of arcs, so readability isn’t the best but it’s not hard either. [rhoalt] does mention that the display is easier to read via blurred camera images rather than visually, which isn’t surprising. We’re long used to seeing numbers composed of straight line segments, so arc segmented digits do look weird. But we wouldn’t have known this if [rhoalt] hadn’t shown us, right ? Maybe a thicker diffuser with separator baffles may improve the readability.

Each digit is made using one pair of Neopixel rings, stacked to form a figure of eight. All the digits are composed of arcs, so readability isn’t the best but it’s not hard either. [rhoalt] does mention that the display is easier to read via blurred camera images rather than visually, which isn’t surprising. We’re long used to seeing numbers composed of straight line segments, so arc segmented digits do look weird. But we wouldn’t have known this if [rhoalt] hadn’t shown us, right ? Maybe a thicker diffuser with separator baffles may improve the readability.

For the display, he’s using eight big vintage Burroughs B7971 Nixie Tubes. These aren’t easy to source, and current prices hover around $100 each if you can find them. The 170V DC needed to run each tube comes from a set of six

For the display, he’s using eight big vintage Burroughs B7971 Nixie Tubes. These aren’t easy to source, and current prices hover around $100 each if you can find them. The 170V DC needed to run each tube comes from a set of six