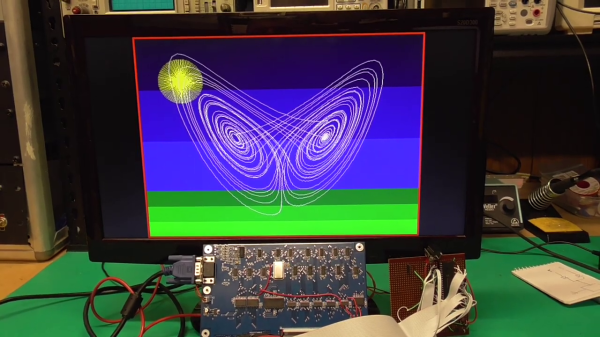

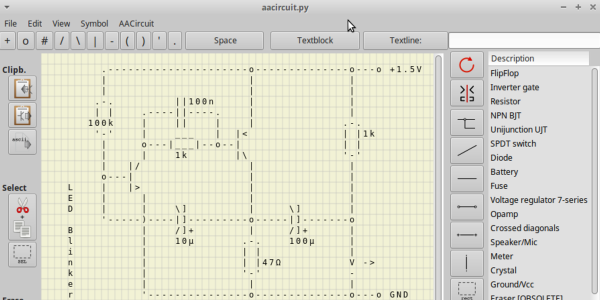

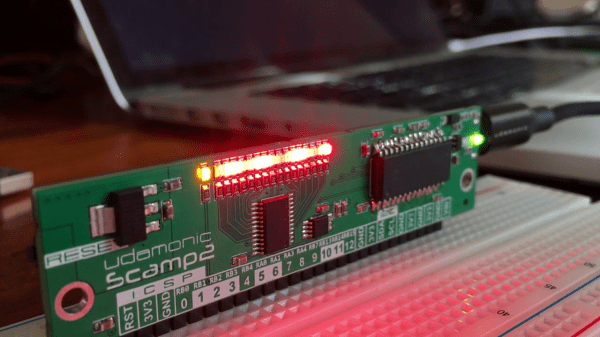

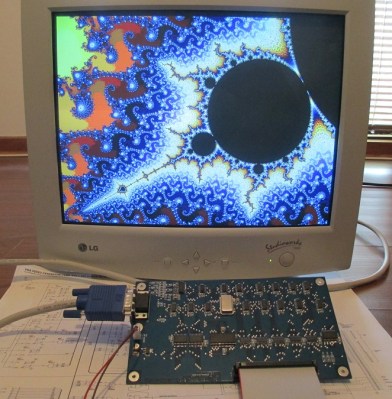

Feeling nostalgic we presume, [Glen Kleinschmidt] set out to build a 640x480x64 VGA controller card from discrete logic chips. If we ignore the 512Kx8 Cypress SRAM video memory, he succeeds, too — and on a very readable, single page A3 schematic. The goal is to interface some of his older 8-bit machines, like the TRS-80 Model 1 and the BBC Micro, but for now he’s running a demo using a 20+ year old PIC16F877 micro.

[Glen] provides all the schematics, Gerbers, and C source code on his website should you be inclined to reproduce one for yourself. He has three versions in the works, with various capabilities (there’s a table on his website). As an alternative, one could always use an FPGA or a custom-built chip such as the SSD1963 to generate video for these micros, but sometimes the urge to go retro is too great to resist. We get the feeling that for [Glen], this is a project unto itself, and being able to interface it to his 8-bit computers is just a convenient excuse.

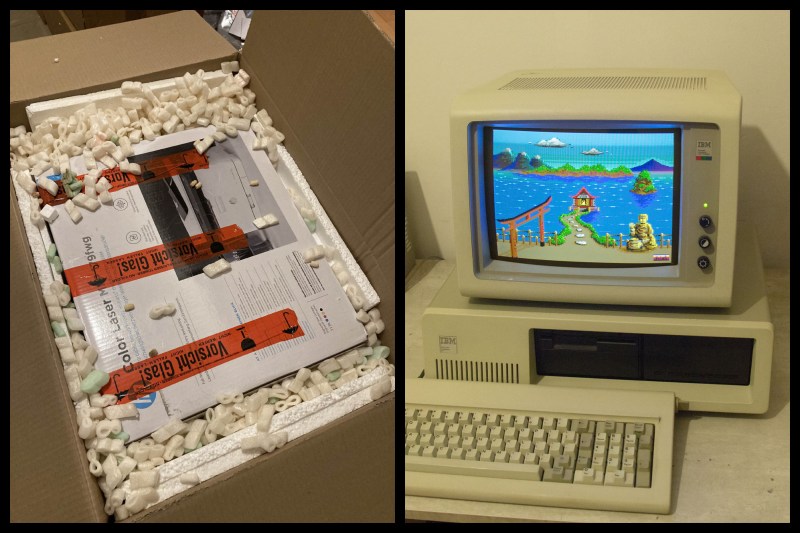

This isn’t [Glen]’s first retro project, either. Check out his analog computer “bouncing ball” project we covered back in 2017. Have you struggled with the build vs. buy decision, and how do you decide?