It’s been a long time since computer hobbyists stored their programs and data on cassette tapes. But because floppy drives were expensive peripherals and hard drives were still a long way from being the commodity they are today, cassettes enjoyed a long run at the top of the bulk data storage heap.

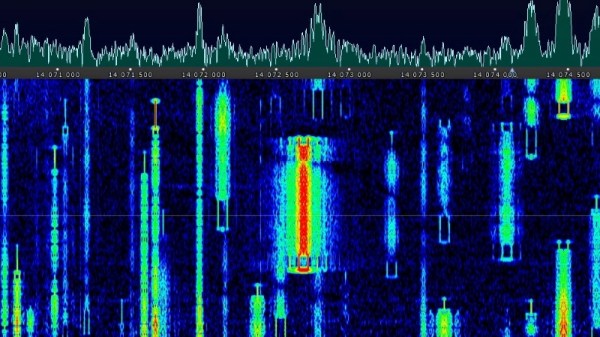

Celebrating that success by exploring the technology of cassette data storage is the idea behind [Greg Strike]’s Kansas City decoder project, which he hopes to use with his [Ben Eater]-style 6502 computer. The video below explains the Kansas City standard in some detail, and includes some interesting historical context we really hadn’t delved into before. There are also some good technical details on the modulation scheme KCS used, which [Greg] used to base his build. After a failed attempt to use an LM567 tone decoder chip, he stumbled upon [matseng]’s KCSViewer project, which decodes KCS-encoded audio signals using nothing but discrete components.

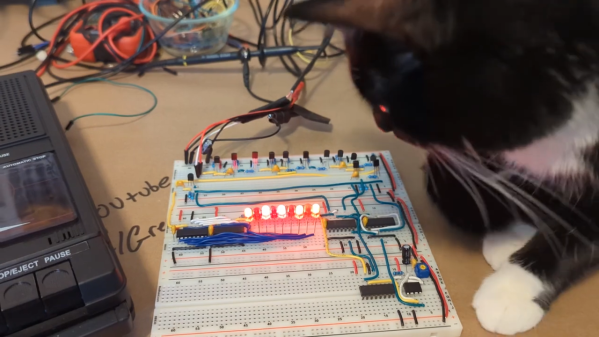

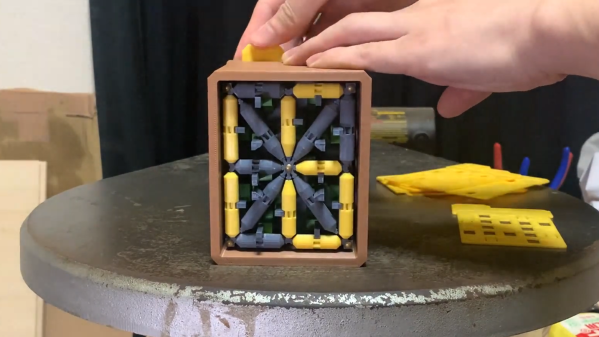

[Greg]’s prototype has a comparator to convert sine waves to square waves, followed by pair of monostable timers, each tuned to either the high or low frequency defined in the KCS specs. A test signal created using Audacity — is there anything it can’t do? — was successfully decoded, providing proof of concept for the project’s first phase. We’re looking forward to the rest of the series, which will turn this into an actual decoder, and presumably add an encoder as well.

Listeners of the Hackaday Podcast may recall we experimented with using KCS to hide some data within an episode a few months back.

Continue reading “A Cassette Interface For A 6502 Breadboard Computer, Kansas City-Style”