With few exceptions, power transmission is a field where wobbling is a bad thing. We generally want everything running straight and true, with gears and wheels perfectly perpendicular to their shafts, with everything moving smoothly and evenly. That’s not always the case, though, as this pericyclic gearbox demonstrates.

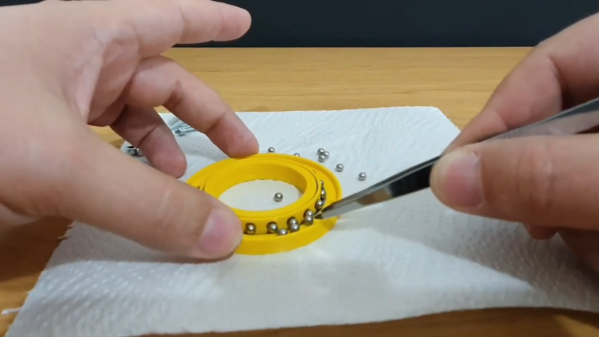

Although most of the components in [Retsetman] model gearboxes seem familiar enough — it’s mostly just a collection of bevel gears, like you’d see inside a differential — it’s their arrangement that makes everything work. More specifically, it’s the shaft upon which the bevel gears ride, which has a section that is tilted relative to the axis of the shaft. It’s just a couple of degrees, but that small bit of inclination, called nutation, makes the ring gear riding on it wobble as the shaft rotates, allowing it to mesh with one or more ring gears that are perpendicular to the shaft. This engages a few teeth at a time, transferring torque from one gear to another. It’s easier to visualize than it is to explain, so check out the video below.

Gearboxes like these have a lot of interesting properties, with the main one being gear ratio. [Retsetman] achieved a 400:1 ratio with just 3D printed parts, which of course impose their own limitations. But he was still able to apply some pretty serious torque. The arrangement is not without its drawbacks, of course, with the wobbling bits naturally causing unwelcome vibrations. That can be mitigated to some degree using multiple rotatins elements that offset each other, but that only seems to reduce vibration, not eliminate it.

[Retsetman] is no stranger to interesting gearboxes, of course, with his toothless magnetic gearboxes coming to mind. And this isn’t the only time we’ve seen gearboxes go all wobbly, either.

Continue reading “Bent Shaft Isn’t A Bad Thing For This Pericyclic Gearbox”