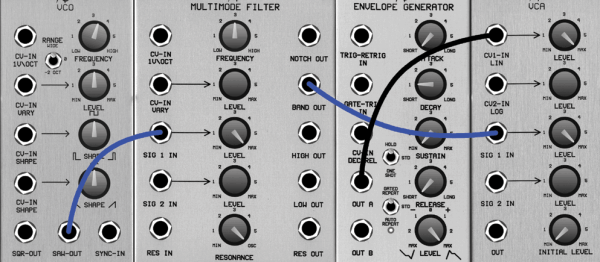

If you’re at all interested in synthesizers, but haven’t gotten as deep into programming them as you’d like, you absolutely need to check out the old “Synth Secrets” column from Sound on Sound magazine. Across 63(!) articles, the author [Gordon Reid] takes a practical approach to learning synthesizers: trying to copy the sound of one real instrument at a time, with concrete examples built up on one particular synthesizer.

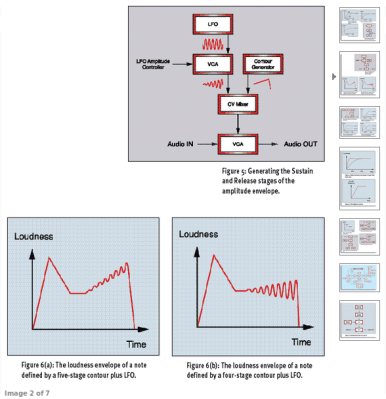

[Gordon]’s approach to synthesis is straightforward, but that’s exactly what makes it useful. After the first couple articles, which introduce you to the common functions of many synthesizers, most articles follow a simple pattern: listen to the instrument’s characteristic sounds, look to the physics behind how it produces them, and then figure out how to replicate as much of the sound as is necessary (or possible) to capture the essence of the instrument. Sometimes when the instrument’s sounds are particularly complex, as in this series of articles on the violin, he’ll break this simple formula up across multiple articles.

[Gordon]’s approach to synthesis is straightforward, but that’s exactly what makes it useful. After the first couple articles, which introduce you to the common functions of many synthesizers, most articles follow a simple pattern: listen to the instrument’s characteristic sounds, look to the physics behind how it produces them, and then figure out how to replicate as much of the sound as is necessary (or possible) to capture the essence of the instrument. Sometimes when the instrument’s sounds are particularly complex, as in this series of articles on the violin, he’ll break this simple formula up across multiple articles.

Now you might complain that you don’t have a Korg MS-20 or an ARP Odyssey or whatever particular old synth is being used in any particular article. But the “Secrets” are actually so fundamental, and by-and-large worked out on such simple analog synths, that even if you can’t make exactly the same sounds as [Gordon] does, you’ll understand how he got where he got, you’ll probably get pretty close, and you’ll have tuned up your ears along the way.

Plus, you’ll learn a tremendous amount about the character and capabilities of your synthesizer by trying. Working through the “Synth Secrets” examples would be a great way to get to know a new synth in your rack, even if you’re only into space noise and not interested in reproducing real instruments.

But if you are into space noise, also check out our own Logic Noise series. You won’t learn anything about real instruments, but you’ll learn a heck of a lot about the 4000-series logic chips and the abuse thereof.

Thanks [Greg Kennedy] for reminding us of this gem, and for re-installing the “Synth Secrets” bee in our bonnet!