A car is a rolling pile of hundreds of microcontrollers these days — just ask any greybeard mechanic and he’ll start his “carburetor” rant. All of these systems and sub-systems need to talk to each other in an electrically hostile environment, and it’s not an exaggeration to say that miscommunication, or even delayed communication, can have serious consequences. In-car networking is serious business. Mass production of cars makes many of the relevant transceiver ICs cheap for the non-automotive hardware hacker. So why don’t we see more hacker projects that leverage this tremendous resource base?

The backbone of a car’s network is the Controller Area Network (CAN). Hackaday’s own [Eric Evenchick] is a car-hacker extraordinaire, and wrote up most everything you’d want to know about the CAN bus in a multipart series that you’ll definitely want to bookmark for reading later. The engine, brakes, doors, and all instrumentation data goes over (differential) CAN. It’s fast and high reliability. It’s also complicated and a bit expensive to implement.

In the late 1990, many manufacturers had their own proprietary bus protocols running alongside CAN for the non-critical parts of the automotive network: how a door-mounted console speaks to the door-lock driver and window motors, for instance. It isn’t worth cluttering up the main CAN bus with non-critical and local communications like that, so sub-networks were spun off the main CAN. These didn’t need the speed or reliability guarantees of the main network, and for cost reasons they had to be simple to implement. The smallest microcontroller should suffice to roll a window up and down, right?

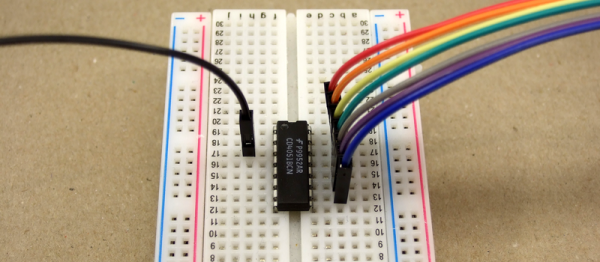

In the early 2000s, the Local Interconnect Network (LIN) specification standardized one approach to these sub-networks, focusing on low cost of implementation, medium speed, reconfigurability, and predictable behavior for communication between one master microcontroller and a small number of slaves in a cluster. Cheap, simple, implementable on small microcontrollers, and just right for medium-scale projects? A hacker’s dream! Why are you not using LIN in your multiple-micro projects? Let’s dig in and you can see if any of this is useful for you. Continue reading “Embed With Elliot: LIN Is For Hackers”

In the early 2000s, the Local Interconnect Network (LIN) specification standardized one approach to these sub-networks, focusing on low cost of implementation, medium speed, reconfigurability, and predictable behavior for communication between one master microcontroller and a small number of slaves in a cluster. Cheap, simple, implementable on small microcontrollers, and just right for medium-scale projects? A hacker’s dream! Why are you not using LIN in your multiple-micro projects? Let’s dig in and you can see if any of this is useful for you. Continue reading “Embed With Elliot: LIN Is For Hackers”