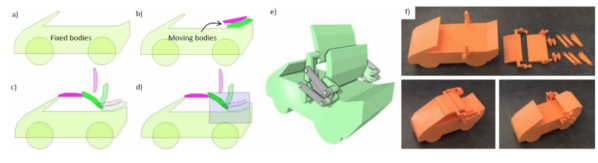

Jokes aside, manually designing linkages that move along specific paths is no easy task. Whether we’re doodling paper sketches or constraining lines in a CAD program, we still need to do the work of actually “imagining” the linkage design. If only there were some sort of tool that would do all that hard imagining work for us! Thankfully, we’re in luck! That’s exactly what researchers [Gen Nishida], [Adrien Bousseau2], and [Daniel G. Aliaga1] at Purdue have done. They’ve designed a software tool that lets us position important bodies in space in particular “key” frames, and then the software simply fills in the linkage for you!

To start the design process, the user inputs a few candidate locations that their solid bodies need to reach in the final linkage path. From here, these locations get fed to a particle filter. This particle filter seeds thousands of semi-random linkage configurations at small timesteps, selects some of the best-matching ones that most closely approximate the required body locations, removes the lesser-scoring results, re-creates a new set of possible joint configurations based on the best matching ones, and repeats until the tool converges on a linkage that respects our input key frames.

Like a brute force search, this solution takes lots and lots of samples to find a solution, but unlike a brute force search, trials iteratively improve, enabling the software to converge closer and closer to a final solution. Under the hood, the software needs to actually simulate these candidate linkage in order to grade them. It’s in this step that the team wrote in additional checks to remove impossible linkages like self-intersecting joints from this linkage “gene pool” before reseeding them. The result is a tool that does all that trial-and-error scratchwork for you–no brain cycles. For more details, have a peek at their (open access!) paper.

Design software that augments our mechanical design capabilities is a rare gem on these pages, and this one is no exception. If your curious to play with other useful linkages simulating tools, have a go at Linkage Designer. And if you’re in the mood for other tools that fill in the blanks, check out this machine learning algorithm that literally fills in footage between frames in a video feed.

Continue reading “Linkage Inferring Software Handwaves Away The Hard Stuff”

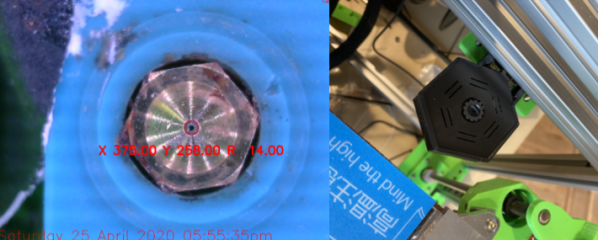

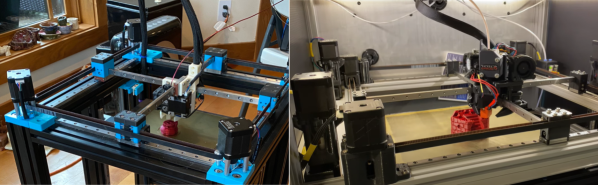

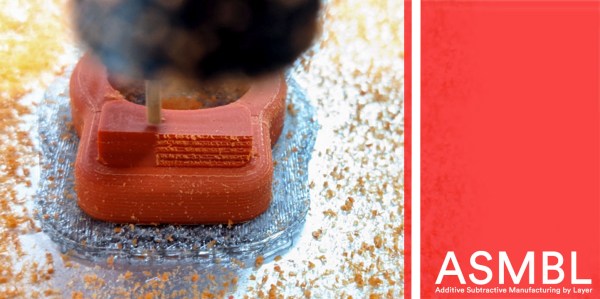

Dubbed ASMBL (Additive/Subtractive Machining By Layer), the process is actually the merging of two complimentary processes combined into one workflow to produce a single part. Here, vanilla 3D printing does the work of producing the part’s overall shape. But at the end of every layer, an endmill enters the workspace and trims down the imperfections of the perimeter with a light finishing pass while local suction pulls away the debris. This concept of mixing og coarse and fine manufacturing processes to produce parts quickly is a re-imagining of a tried-and-true industrial process called near-net-shape manufacturing. However, unlike the industrial process, which happens across separate machines on a large manufacturing facility, E3D’s ASMBL takes place in a single machine that can change tools automatically. The result is that you can kick off a process and then wander back a few hours (and a few hundred tool changes) later to a finished part with machined tolerances.

Dubbed ASMBL (Additive/Subtractive Machining By Layer), the process is actually the merging of two complimentary processes combined into one workflow to produce a single part. Here, vanilla 3D printing does the work of producing the part’s overall shape. But at the end of every layer, an endmill enters the workspace and trims down the imperfections of the perimeter with a light finishing pass while local suction pulls away the debris. This concept of mixing og coarse and fine manufacturing processes to produce parts quickly is a re-imagining of a tried-and-true industrial process called near-net-shape manufacturing. However, unlike the industrial process, which happens across separate machines on a large manufacturing facility, E3D’s ASMBL takes place in a single machine that can change tools automatically. The result is that you can kick off a process and then wander back a few hours (and a few hundred tool changes) later to a finished part with machined tolerances.