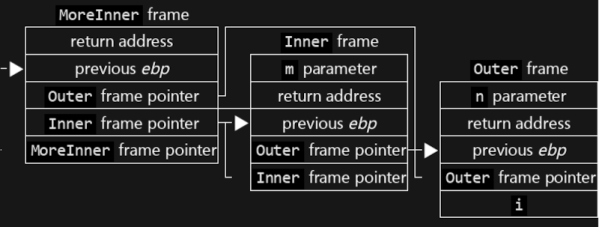

[Raymond Chen] wondered why the x86 ENTER instruction had a strange second parameter that seems to always be set to zero. If you’ve ever wondered, [Raymond] explains what he learned in a recent blog post.

If you’ve ever taken apart the output of a C compiler or written assembly programs, you probably know that ENTER is supposed to set up a new stack frame. Presumably, you are in a subroutine, and some arguments were pushed on the stack for you. The instruction puts the pointer to those arguments in EBP and then adjusts the stack pointer to account for your local variables. That local variable size is the first argument to ENTER.

The reason you rarely see it set to a non-zero value is that the final argument is made for other languages that are not as frequently seen these days. In a simple way of thinking, C functions live at a global scope. Sure, there are namespaces and methods for classes and instances. But you don’t normally have a C compiler that allows a function to define another function, right?

Turns out, gcc does support this as an extension (but not g++). However, looking at the output code shows it doesn’t use this feature, but it could. The idea is that a nested function can “see” any local variables that belong to the enclosing function. This works, for example, if you allow gcc to use its extensions:

#include <stdio.h>

void test()

{

int a=10;

/* nested function */

void testloop(int n)

{

int x=a;

while(n--) printf("%d\n",x);

}

testloop(3);

printf("Again\n");

testloop(2);

printf("and now\n");

a=33;

testloop(5);

}

void main(int argc, char*argv[])

{

test();

}

Continue reading “X86 ENTER: What’s That Second Parameter?” →