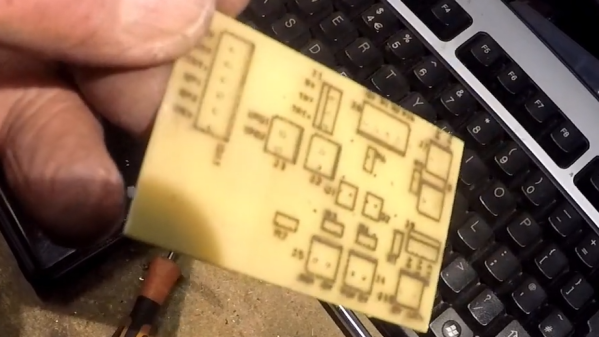

It is funny how when you first start doing something, you have so many misconceptions that you have to discard. When you look back on it, it always seems like you should have known better. That was the case when I first got a low-end laser cutter. When you want to cut or engrave something, it has to be in just the right spot. It is like hanging a picture. You can get really close, but if it is off just a little bit, people will notice.

The big commercial units I’ve been around all had cameras that were in a fixed position and were calibrated. So the software didn’t show you a representation of the bed. It showed you the bed. The real bed plus whatever was on it. Getting things lined up was simply a matter of dragging everything around until it looked right on the screen.

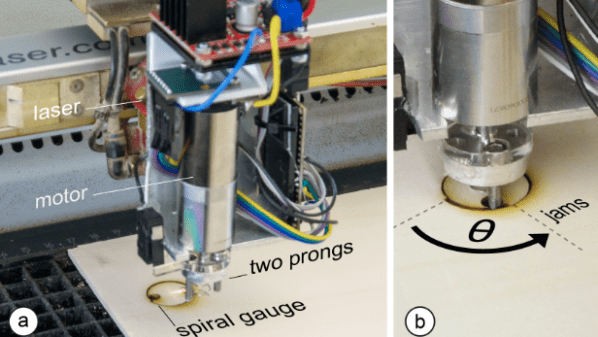

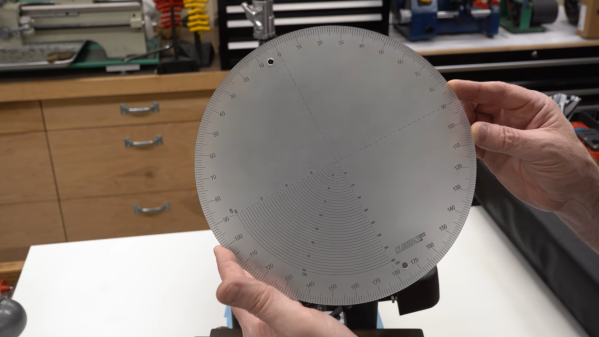

Today, some cheap laser cutters have cameras, and you can probably add one to those that don’t. But you still don’t need it. My Ourtur Laser Master 3 has nothing fancy, and while I didn’t always tackle it the best way, my current method works well enough. In addition, I recently got a chance to try an XTool S1. It isn’t that cheap, but it doesn’t have a camera. Interestingly, though, there are two different ways of laying things out that also work. However, you can still do it the old-fashioned way, too. Continue reading “Laser Cutters: Where’s The Point?”