According to [Asianometry], in 1986 the Soviet Union had about 10,000 computers. At the same time, the United States had 1.3 million! The USSR was hardly a backward country — they’d launched Sputnik and made many advances in science and mathematics. Why didn’t they have more computers? The story is interesting and you can see it in the video below.

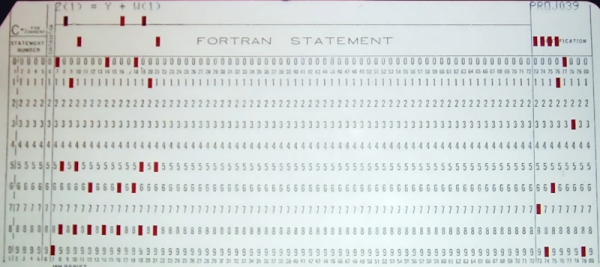

Apparently when news of ENIAC reached the USSR, many dismissed it as fanciful propaganda. However, there were some who thought computing would be the future. Sergey Lebedev in Ukraine built a “small” machine around 1951. Small, of course, is relative since the machine had 6,000 tubes in it. It performed 250,000 calculations for artillery tables in about 2 and half hours.

The success of this computer led to two teams being asked to build two different machines. Although one of the machines was less capable, the better machine needed a part they could only get from the other team which they withheld, forcing them to use outdated — even then — mercury delay lines for storage.

The more sophisticated machine, the BESM-1, didn’t perform well thanks to this substitution and so the competitor, STRELA, was selected. However, it broke down frequently and was unable to handle certain computations. Finally, the BESM-1 was completed and was the fastest computer in Europe for several years starting in 1955.

By 1959, the Soviets produced $59 million worth of computer parts compared to the US’s output of around $1 billion. There are many reasons for the limited supply and limited demand that you’ll hear about in the video. In particular, there was little commercial demand for computers in the Soviet Union. Nearly all the computer usage was in the military and academia.

Eventually, the Russians wound up buying and copying the IBM 360. Not all of the engineers thought this was a good idea, but it did have the advantage of allowing for existing software to run. The US government tried to forbid IBM from exporting key items, so ICL — a UK company — offered up their IBM 360-compatible system.

The Soviets have been known to borrow tech before. Not that the west didn’t do some borrowing, too, at least temporarily.

Continue reading “A Look Back At The USSR Computer Industry”