Software defined radio picked up a lot of popularity when it was discovered that cheap USB TV tuners were functional bits of hardware that could become SDRs. It’s the software that makes this possible, and when it comes to SDR software, there’s no better tool than GNU Radio. For this week’s Hack Chat we’re going to sit down with some of the people behind this awesome software tool and pick their brains.

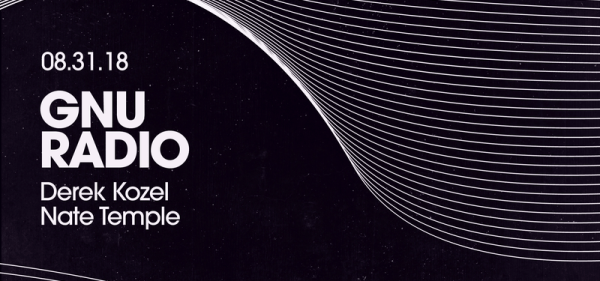

Our guests for this week’s Hack Chat will be Derek Kozel and Nate Temple, officers of the GNU Radio project. They’re also organizers of this year’s GNU Radio Conference. Also joining in on the Hack Chat will be Martin Braun, community manager, PyBOMBS maintainer, and GNU Radio Foundation officer.

Our guests for this week’s Hack Chat will be Derek Kozel and Nate Temple, officers of the GNU Radio project. They’re also organizers of this year’s GNU Radio Conference. Also joining in on the Hack Chat will be Martin Braun, community manager, PyBOMBS maintainer, and GNU Radio Foundation officer.

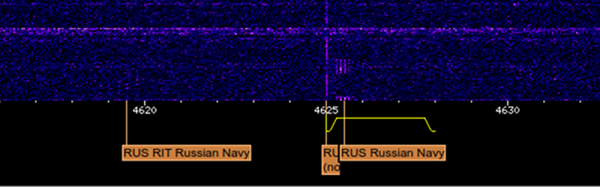

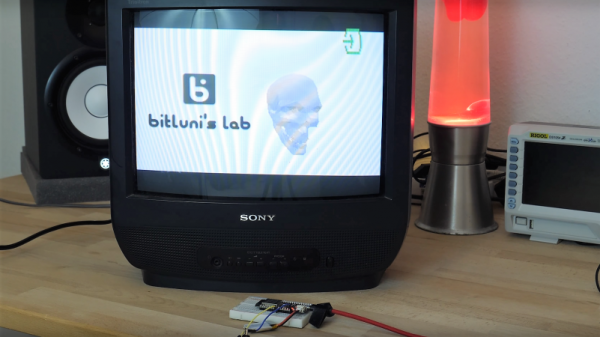

GNU Radio is perhaps the most important bit of any software defined radio toolchain. This is the software that provides signal processing blocks to implement software defined radios. GNU radio is how you take a TV tuner USB dongle and pull images from satellites. You can use it for simulation, and GNU Radio is widely used by hobbyists, academics, and by people in industry.

For this week’s Hack Chat, we’re going to be talking all about GNU Radio. What can you do with it? Was the interface really inspired by MaxMSP? All that and more in this week’s Hack Chat.

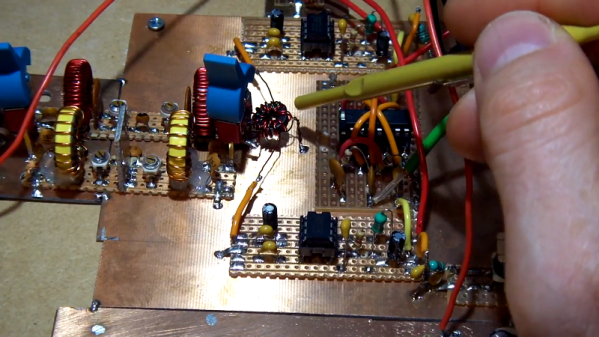

- Various bits of hardware that make GNU Radio work

- The core process of writing modules

- Upcoming features of GNU Radio

You are, of course, encouraged to add your own questions to the discussion. You can do that by leaving a comment on the GNU Radio Hack Chat Event Page and we’ll put that in the queue for the Hack Chat discussion.

Our Hack Chats are live community events on the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This week is just like any other, and we’ll be gathering ’round our video terminals at noon, Pacific, on Friday, August 31st. Need a countdown timer? We should look into hosting these countdown timers on hackaday.io, actually.

Click that speech bubble to the right, and you’ll be taken directly to the Hack Chat group on Hackaday.io.

You don’t have to wait until Friday; join whenever you want and you can see what the community is talking about.

![[M0CVO]'s Tweet that started it all](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/screenshot-2017-10-31-nigel-booth-on-twitter.png?w=298)