Netbooks are dead, long live the Chromebook. Lewin Day wrote up a proper trip down Netbook Nostalgia Lane earlier this month. That’s required reading, go check it out and come back. You’re back? Good. Today I’m making the case that the Chromebook is the rightful heir to the netbook crown, and to realize its potential I’ll show you how to wring every bit of Linuxy goodness out of your Chromebook.

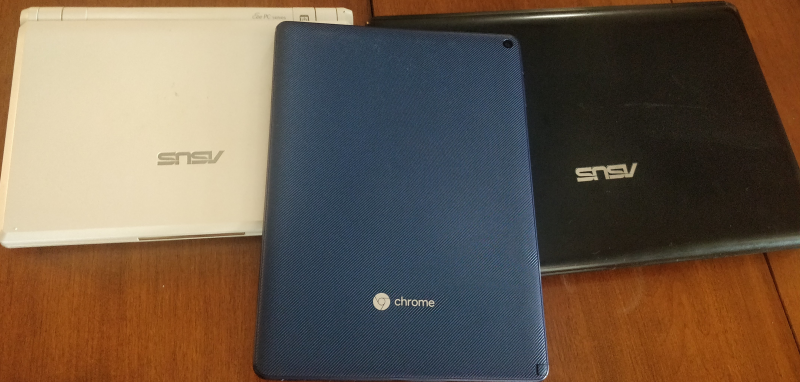

I too was a netbook connoisseur, starting with an Asus Eee 901 way back in 2009. Since then, I’ve also been the proud owner of an Eee PC 1215B, which still sees occasional use. Only recently did I finally bite the bullet and replace it with an AMD based Dell laptop for work.

For the longest time, I’ve been intrigued by a good friend who went the Chromebook route. He uses a Samsung Chromebook Plus, and is constantly using it to SSH into his development machines. After reading Lewin’s article, I got the netbook bug again, and decided to see if a Chromebook would fill the niche. I ended up with the Acer Chromebook Tab 10, codename Scarlet. The price was right, and the tablet form factor is perfect for referencing PDFs.

The default ChromeOS experience isn’t terrible. You have the functionality of desktop Chrome, as well as the ability to run virtually any Android app. It’s a good start, but hardly the hacker’s playground that a Linux netbook once was. But we can still get our Linux on with this hardware. There are three separate approaches to making a Chromebook your own virtual hackspace: Crostini, Crouton, and full OS replacement.

Continue reading “Netbooks: The Next Generation — Chromebooks”