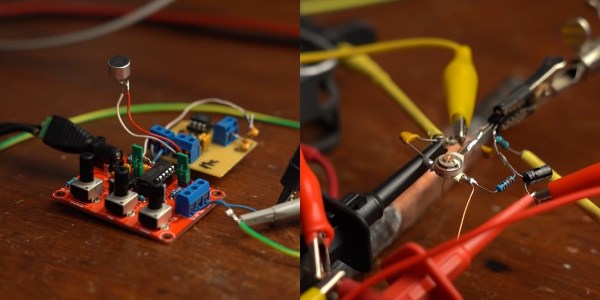

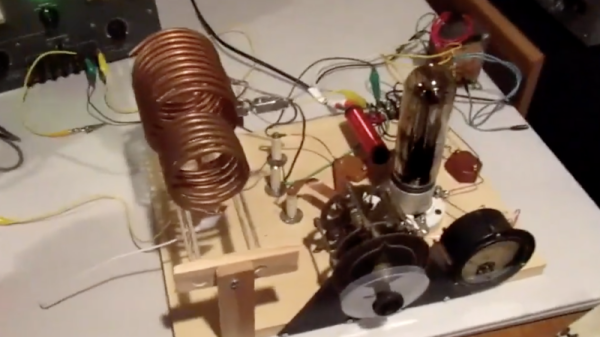

Had the pandemic not upended many of this summer’s fun and games, many of my friends would have made a trip to the MCH hacker camp in the Netherlands earlier this month. I had an idea for a game for the event, a friend and I were going to secrete a set of those low-power FM transmitters as numbers stations around the camp for players to find and solve the numerical puzzles they would transmit. I even bought a few cheap FM transmitter modules from China for evaluation, and had some fun sending a chiptune Rick Astley across a housing estate in Northamptonshire.

To me as someone who grew up with FM radio and whose teen years played out to the sounds of BBC Radio 1 FM it made absolute sense to do a puzzle in this way, but it was my personal reminder of advancing years to find that some of my friends differed on the matter. Sure, they thought it was a great idea, but they gently reminded me that the kids don’t listen to any sort of conventional broadcast radio these days, instead they stream their music, so very few of them would have the means for listening to my numbers stations. Even for me it’s something I only use for BBC Radio 4 in the car, and to traverse the remainder of the FM dial is to hear a selection of easy listening, oldies, and classical music. It’s becoming an older person’s medium, and it’s inevitable that like AM before it, it will eventually wane.

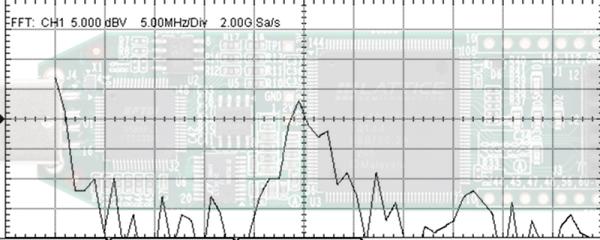

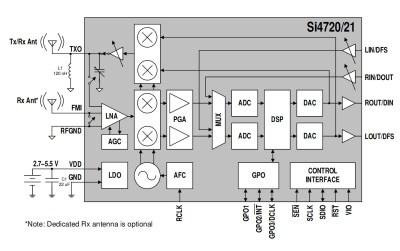

There are two angles to this that might detain the casual hacker; first what it will mean from a broadcasting and radio spectrum perspective, and then how it is already influencing some of our projects.

Continue reading “FM Radio, The Choice Of An Old Generation”