A few weeks ago, Amazon’s crack marketing AI decided to recommend a few books for me. That AI must be getting better because instead of the latest special-edition Twilight books, I was greeted with this:

“The asteroid was called the Hand of God when it hit.”

That’s the first sentence of The Bridge, a new Sci-Fi book by Leonard Petracci. If you think that line sucks you in, wait until you read the whole first chapter.

The Bridge is solidly in the generation ship trope. A voyage hundreds or even thousands of years long, with no sleep or stasis pods. The original crew knows they have no hope of seeing their destination, nor will their children and grandchildren. Heinlein delved into it with Orphans of the Sky. Even Robert Goddard himself discussed generation ships in The Last Migration.

I wouldn’t call The Bridge hard Sci-Fi — and that’s perfectly fine. Leonard isn’t going for scientific accuracy. It’s a great character driven story. If you enjoyed a book like Ready Player One, you’ll probably enjoy this.

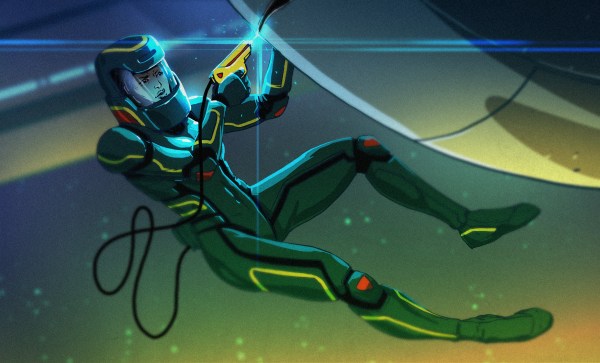

The Bridge Is the story of Dandelion 14, a ship carrying people of Earth to a new planet. At some point during the journey, Dandelion 14 was struck by an asteroid, which split the ship in two. Only a few wires and cables keep the halves of the ship together. The crew on both sides of the ship survived, but they had no way to communicate. They do catch glimpses of each other in the windows though.

Much of the story is told in the first person by Horatius, a young man born hundreds of years after the asteroid strike. Horatius’ side of the ship has a population of one thousand, carefully measured at each census. They’ve lost knowledge of how to operate the ship’s systems, but they are surviving. Most of the population are gardeners, but there are doctors, cooks, porters, and a few historians. At four years old, Horatius is selected to become a gardener, like his father was before him. But Horatius has higher aspirations. He longs to become a historian to learn the secrets of the generations that came before him and to write his own story down for those who will come after.

Horatius sees the faces of the people on the other side of the ship as well. Gaunt, hungry, often fighting with knives or other weapons. A stark contrast to the well-fed people on his side of the vessel. The exception is one red-haired girl about his age. He often finds her staring back at him, watching him.

Horatius might have been chosen as a gardener, but he’s clever — a fact that sometimes gets him in trouble. His life takes an abrupt turn when the sleeping ship awakens with an announcement blaring “Systems Rebooting, Ship damage assessed. Reuniting the two halves of the ship and restoring airlock, approximately twenty-four hours until complete.”

The hardest part of writing a book review is not giving too much away. While I won’t tell you much more about the plot for The Bridge, I can tell a bit about how the book came about. You might call this book a hack of the publishing system. Leonard Petracci is also known as leoduhvinci on Reddit. The Bridge started life as Leonard’s response to a post on /r/writingprompts. The prompt went like this:

After almost 1,000 years the population of a generation ship has lost the ability to understand most technology and now lives at a pre-industrial level. Today the ship reaches its destination and the automated systems come back online.

Leonard ’s response to the prompt shot straight to the top, and became the first chapter of The Bridge. Chapter 2 followed soon after. In only a few months, the book was complete. Available on Reddit, and on Leonard’s website. The Bridge is also available on Amazon for Kindle, and on paper from Amazon’s CreateSpace.

The only real criticism I have about The Bridge is the ending. The book’s resolution felt a bit rushed. It would have been nice to have a few more pages telling us what happened to the characters after the major events of the book. Leonard is planning a sequel though, and he teases this in the final pages.

You can start reading The Bridge right now on Leonard’s website. He has the entire book online for free for a few more weeks. If you’ve missed the free period, the Kindle edition is currently $2.99.

Liquid rocket propellant was in two parts: a fuel and an oxidizer. The combination is hypergolic; that is, the two spontaneously ignite and burn upon contact with each other. As an example of the kinds of details that mattered (i.e. all of them), the combustion process had to be rapid and complete. If the two liquids flow into the combustion chamber and ignite immediately, that’s good. If they form a small puddle and then ignite, that’s bad. There are myriad other considerations as well; the fuel must burn at a manageable temperature (so as not to destroy the motor), the energy density of the fuel must be high enough to be a practical fuel in the first place, and so on.

Liquid rocket propellant was in two parts: a fuel and an oxidizer. The combination is hypergolic; that is, the two spontaneously ignite and burn upon contact with each other. As an example of the kinds of details that mattered (i.e. all of them), the combustion process had to be rapid and complete. If the two liquids flow into the combustion chamber and ignite immediately, that’s good. If they form a small puddle and then ignite, that’s bad. There are myriad other considerations as well; the fuel must burn at a manageable temperature (so as not to destroy the motor), the energy density of the fuel must be high enough to be a practical fuel in the first place, and so on.