It’s not a balloon, however shiny its exterior may seem. This miniature indoor robotic airship created by the University of Auckland mechanical engineering research group [New Dexterity] is an asymmetric system experimenting with the possibilities of an open-source helium-based airship.

Why a helium airship, as opposed to a fixed wing aircraft? The group wanted to experiment with the advantages of lighter-than-air (LTA) travel, namely the higher mobility and looser path planning constraints. Furthermore, LTA airships have a less obstructed field of vision and fewer locomotion issues. While unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) may be capable of hovering in one place, their lift is generated by rotor thrust, which drains their batteries quickly in the order of minutes. LTA airships can hover for longer periods of time.

The design was created for educational and research purposes, focusing on the financial feasibility of manufacturing the platform, the environmental impact of the materials, and the helium loss through the balloon-like envelope. By measuring these parameters, the researchers are able to study the effects of circumstances such as the cost of indoor commercial balloons and the mechanical properties of balloon materials.

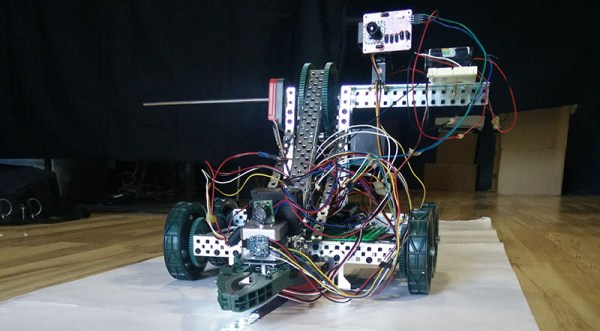

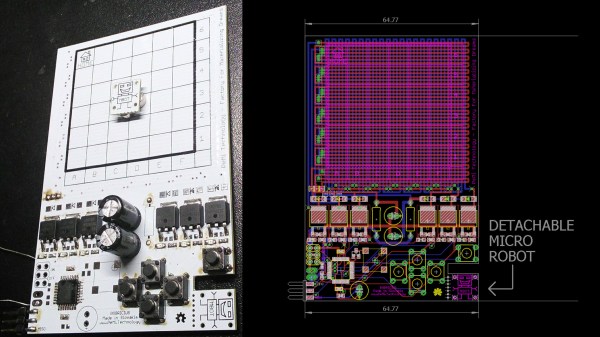

The airship gondola was designed and 3D printed in a modular fashion, then attached to the envelope with Velcro. The placement with respect to the horizontal symmetry of the gondola was done for flight stability, with several configurations tested for the side rotor angle.

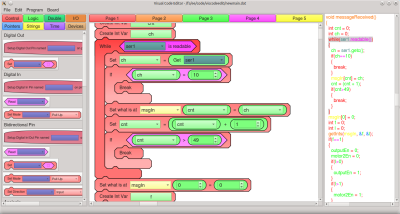

The group open-sourced their CAD files and ROS interface for controlling the airship. They primarily use off-the-shelf components such as Raspberry Pi boards, propellers, a DC single brushed motor driver carrier, and LiPo batteries for a total cost of $90 for the platform, with an addition $20 for the balloon and initial helium filling. The price is comparable to the cost of indoor blimps like the Blimpduino 2.0.

You can check out the completed airship below, where the team demonstrates its path following capabilities based on a carrot chasing path finding algorithm. And if you’re interested in learning more about the gotchas of building lighter-than-air vehicles, check out [Sophi Kravitz’s] blimp talk from Hackaday Belgrade.

Continue reading “Let’s Take A Closer Look At This Robotic Airship”