[Tim aka tp69] built a completely silent desktop computer. It can’t be heard – at all. The average desktop will have several fans whirring inside – cooling the CPU, GPU, SMPS, and probably one more for enclosure circulation – all of which end up making quite a racket, decibel wise. Liquid cooling might help make it quieter, but the pump would still be a source of noise. To completely eliminate noise, you have to get rid of all the rotating / moving parts and use passive cooling.

[Tim]’s computer is built from standard, off-the-shelf parts but what’s interesting for us is the detailed build log. Knowing what goes inside such a build, the decisions required while choosing the parts and the various gotchas that you need to be aware of, all make it an engaging read.

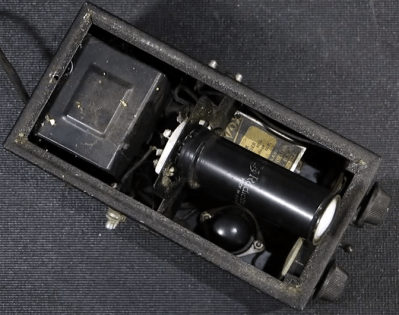

It all starts with a cubic aluminum chassis designed to hold a mini-ITX motherboard. The top and side walls are essentially huge extruded heat sinks designed to efficiently carry heat away from inside the case. The heat is extracted and channeled away to the side panels via heat sinks embedded with sealed copper tubing filled with coolant fluid. Every part, from the motherboard onwards, needs to be selected to fit within the mechanical and thermal constraints of the enclosure. Using an upgrade kit available as an enclosure accessory allows [Tim] to use CPUs rated for a power dissipation of almost 100 W. This not only lets him narrow down his choice of motherboards, but also provides enough overhead for future upgrades. The GPU gets a similar heat extractor kit in exchange for the fan cooling assembly. A fanless power supply, selected for its power capacity as well as high-efficiency even under low loads, keeps the computer humming quietly, figuratively.

It all starts with a cubic aluminum chassis designed to hold a mini-ITX motherboard. The top and side walls are essentially huge extruded heat sinks designed to efficiently carry heat away from inside the case. The heat is extracted and channeled away to the side panels via heat sinks embedded with sealed copper tubing filled with coolant fluid. Every part, from the motherboard onwards, needs to be selected to fit within the mechanical and thermal constraints of the enclosure. Using an upgrade kit available as an enclosure accessory allows [Tim] to use CPUs rated for a power dissipation of almost 100 W. This not only lets him narrow down his choice of motherboards, but also provides enough overhead for future upgrades. The GPU gets a similar heat extractor kit in exchange for the fan cooling assembly. A fanless power supply, selected for its power capacity as well as high-efficiency even under low loads, keeps the computer humming quietly, figuratively.

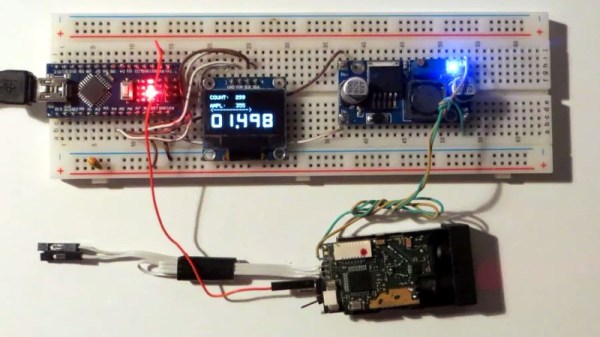

Once the computer was up and running, he spent some time analysing the thermal profile of his system to check if it was really worth all the effort. The numbers and charts look very promising. At 100% load, the AMD Ryzen 5 1600 CPU levelled off at 60 ºC (40 ºC above ambient) without any performance effect. And the outer enclosure temperature was 42 ºC — warm, but not dangerous. Of course, performance hinges around “ambient temperature”, so you have to start getting careful when that goes up.

Getting such silence comes at a price – some may consider it quite steep. [Tim] spent about A$3000 building this whole system, thanks in part due to high GPU prices because of demand from bitcoin mining. But cost is a relative measure. He’s spent less on this system compared to several of his earlier projects and it let’s him enjoy the sounds of nature instead of whiny cooling fans. Some would suggest a pair of ear buds would have been a super cheap solution, but he wanted a quiet computer, not something to cancel out every other sound in his surroundings.