Looking at gasoline prices today, it’s hard to believe that there was a time when 75 cents a gallon seemed outrageous. But that’s the way it was in the 70s, and when it tripped over a dollar, things got pretty dicey. Fuel theft was rampant, both from car fuel tanks — remember lockable gas caps? — and even from gas stations, where drive-offs became common, and unscrupulous employees found ways to trick the system into dispensing free gas.

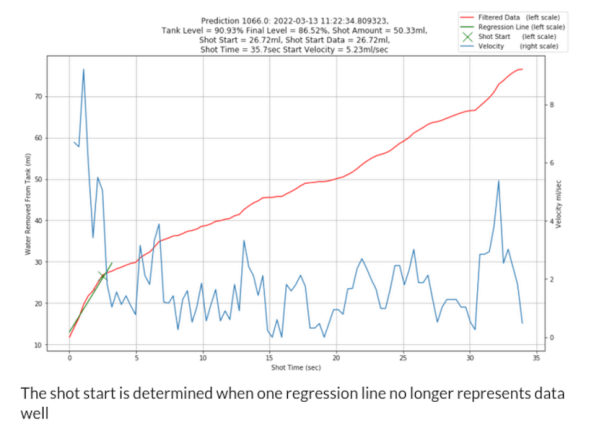

But one method of fuel theft that escaped our attention was the use of CB radios to spoof petrol pumps, which [Ringway Manchester] details in his new video. The scam happened in the early 80s, only a few years after CB became legal in the UK but quite a while since illegal use had exploded. The trick involved a CB transceiver equipped with a so-called “burner,” a high-power and highly illegal linear amplifier used to boost the radiated power of the signal. When keyed up in the vicinity of dispensers with digital controls, the dispensing rate on the display would appear to slow down markedly, while the pump itself stayed at the same speed. The result was more fuel dispensed than the amount reported to the cashier.

If this sounds apocryphal, [Ringway] assures us that it wasn’t. When the spoofing was reported, authorities up to and including Scotland Yard investigated and found that it was indeed plausible. The problem appeared to be the powerful RF signal interfering with the pulses from the flowmeter on the dispenser. The UK had both 27 MHz and 934 MHz CB at the time; [Ringway] isn’t clear which CB band was used for the exploit, but we’d guess it was the former, in which case we can see how the signals would interfere. Another thing to keep in mind is that CB radios in the UK were FM, as opposed to AM and SSB in the United States. So we wonder if the same trick would have worked here.

At the end of the day, no matter how clever you are about it, theft is theft, and things probably aren’t going to go well for you if you try to pull this off today. Besides, it’s not likely that pumps haven’t been hardened against these sorts of attacks. Still, if you want a look inside a modern pump to see if you can find any weaknesses, have at it. Just don’t tell them where you heard about it.

Continue reading “The Inside Story Of The UK’s Great CB Petrol Scam”