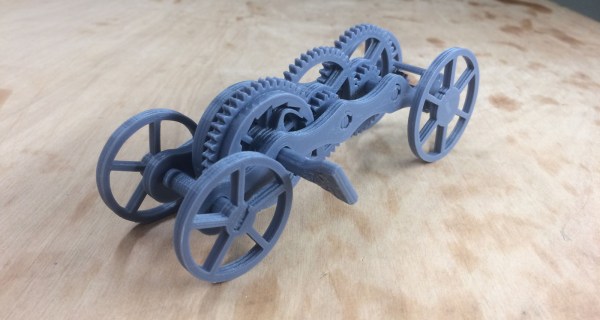

For a hundred years or thereabouts, if you made something out of plastic, you used a mold. Your part would come out of the mold with sprues and flash that had to be removed. Somewhere along the way, someone realized you could use these sprues to hold parts in a frame, and a while later the plastic model was invented. Brilliant. Fast forward a few decades and you have 3D printing. There’s still plastic waste in 3D printing, but it’s in the form of wasteful supports. What if someone designed a 3D printable object like a flat-pack plastic model? That’s what you get when you make a Fully 3D-printable wind up car, just as [Brian Brocken] did. It’s his entry for the Hackaday Prize this year, and it prints out as completely flat parts that snap together into a 3D model.

This 3D model is a fairly standard wind-up car with a plastic spring, escapement, and gear train to drive the rear wheels. Mechanically, there’s nothing too interesting here apart from some nice gears and wheels designed in Fusion 360. Where this build gets serious is how everything is placed on the printer. Every part is contained in one of two frames, laid out to resemble the panels of parts in a traditional plastic model.

These frames, or sprue trees, or whatever we’re calling this technique in the land of 3D printing, form a system of supports that keep all the parts contained until this kit is ready to be assembled. It’s effectively a 3D printable gift card, flat packed for your convenience and ease of shipping. A great project, and one that proves there’s still some innovation left in the world of 3D printing.