Put yourself in [This Old Tony]’s shoes: you get an email out of the blue asking you to take part in making a replica of a 50-year-old spacecraft. Would you believe it? He didn’t, at least not at first, but in the end it proved to be true enough that he made these two assemblies for Project Egress in his own unique style.

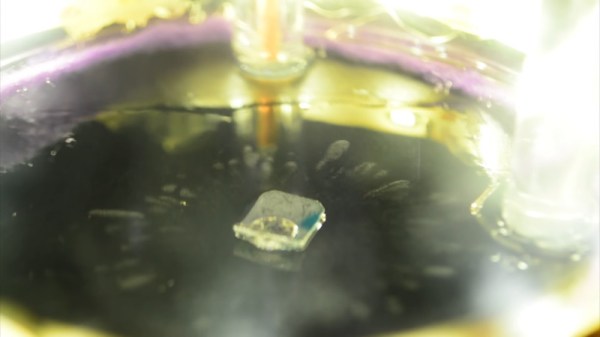

If you haven’t heard of Project Egress, check out our coverage of the initial announcement. The idea is to build a replica of the crew hatch from the Apollo 11 Command Module Columbia, as part of the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 landing next week. [Adam Savage] at Tested has enlisted 44 hackers and makers to help, spreading the work out among the group and letting everyone work in whatever materials and with whatever methods they feel like. [Old Tony], perhaps unsurprisingly, chose mainly Apollo-era dehydrated space-grade aluminum, machined using a combination of manual and CNC machining. We really like the finish he chose – a combination of sandblasting and manual distressing to give it a mission-worn look.

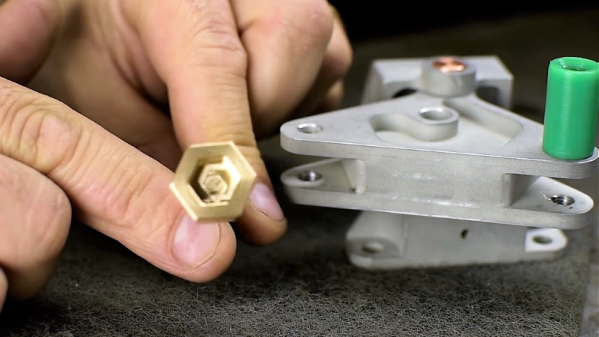

As for exactly what the parts themselves are, the best [Old Tony] could come up with to call them is a bracket and a bell crank. From the original hatch drawings, it looks like there were two bell cranks, which will transmit force around the hatch to the latches that [Fran Blanche], [Joel] and [Bob], and no doubt others have contributed to the build.

We’re eagerly anticipating the final assembly, to be executed by [Adam] live at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum on July 18. Project Egress is as much a celebration of the maker movement as it is a commemoration of Apollo, and we’re pleased that people will get a chance to see the fruits of the labors of all these hackers in so public a forum.

Continue reading “Project Egress: A Bracket And A Bell Crank For The Latches”