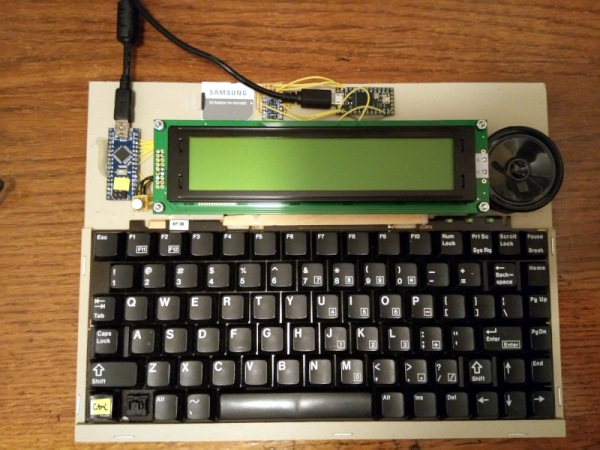

It’s quite probable that any of you who have built a keyboard will have done so using a matrix of keys connected to a microcontroller, or if you are old-school, a microprocessor. A CPU can scan the keyboard matrix with ease, and pass whatever is typed either to whatever software it is running, or to a host computer. There was a time however when available CPUs were not considered powerful enough to do all this and also perform a useful task, so a keyboard would have its own decoder chip that would output ASCII over a parallel interface. It’s an era [John Calhoun] harks back to with Adam74, a little ASCII terminal which takes its input from that 7-bit parallel port.

In the place of a forest of TTL chips which might have graced the originals, within that attractive curved laser cut acrylic case is an LCD display and a Teensy microcontroller board. There’s a level shifter for the classic 5 volt logic, and of course a small buzzer for the essential BEL character. In these days when a parallel interface is relatively rare, he describes the rediscovery of alternate earth lines in a ribbon cable to minimize cross-talk. Should you wish to try your own, everything can be found on GitHub.

All in all it’s a fun way to rediscover an old idea.