There’s nothing quite like a real Christmas tree, but as anyone who’s had one will know there’s also nothing like the quantity of needles that a real tree can shed when it runs short of water. It’s a problem [RK] has tackled, with a Christmas tree water level monitor that has integration with Adafruit’s cloud service to give a handy phone notification when more watering is required.

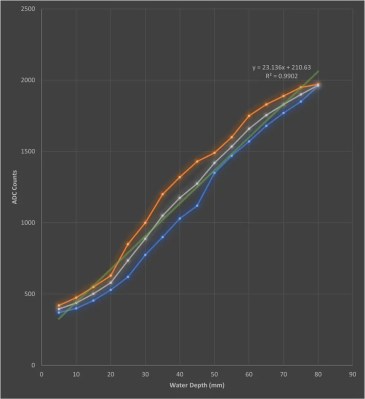

The real interest in this project lies in the sensor development path. There are multiple ways of water level sensing from floats and switches through resistive and light scattering techniques, but he’s taken the brave step of using a capacitive approach. Water can be used as a dielectric between two parallel metal plates, and the level of the water varies the capacitance. Sadly the water from your tap is also a pretty good conductor, so the first attempt at a capacitive sensor was not effective. This was remedied with a polythene “sock” for each electrode constructed with the help of a heat sealer. The measurement circuit was simply a capacitive divider fed with a square wave, from which an Adafruit Huzzah board could easily derive an amplitude reading that was proportional to the water level. The board then sends its readings to Adafruit.io, from which a message can be sent to a Slack channel with the notification enabled. All in all a very handy solution.

The real interest in this project lies in the sensor development path. There are multiple ways of water level sensing from floats and switches through resistive and light scattering techniques, but he’s taken the brave step of using a capacitive approach. Water can be used as a dielectric between two parallel metal plates, and the level of the water varies the capacitance. Sadly the water from your tap is also a pretty good conductor, so the first attempt at a capacitive sensor was not effective. This was remedied with a polythene “sock” for each electrode constructed with the help of a heat sealer. The measurement circuit was simply a capacitive divider fed with a square wave, from which an Adafruit Huzzah board could easily derive an amplitude reading that was proportional to the water level. The board then sends its readings to Adafruit.io, from which a message can be sent to a Slack channel with the notification enabled. All in all a very handy solution.

Plant care is a long-running theme in Hackaday projects, but not all of them need a microcontroller.