If you are a maker, chances are that you will be exposed to unhealthy fumes at some point during your ventures. Whether they involve soldering, treating wood, laser cutting, or 3D printing, it is in your best interest to do so in a well ventilated environment. What seems like sound advice in theory though is unfortunately not always a given in practice — in many cases, the workspace simply lacks the possibility, especially for hobbyists tinkering in their homes. In other cases, the air circulation is adequate, but the extraction itself could be more efficient by drawing out the fumes right where they occur. The latter was the case for [Zander] when he decided to build his own flexible hose fume extractor that he intends to use for anything from soldering to chemistry experiments.

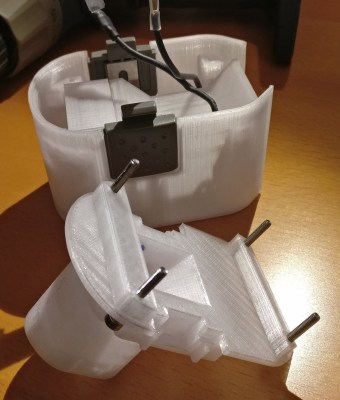

Built around not much more than an AC fan, flex duct, and activated carbon, [Zander] designed and 3D printed all other required parts that turns it into an extractor. Equipped with a pre-filter to hold back all bigger particles before they hit the fan, the air flow is guided either through the active carbon filter, or attached to another flex duct for further venting. You can see more details of his build and how it works in the video after the break.

Workspace safety is often still overlooked by hobbyists, but improved air circulation doesn’t even need to be that complex for starters. There’s also more to read about fumes and other hazardous particles in a maker environment, and how to handle them.

Continue reading “Repairs You Can Print: Take A Deep Breath Thanks To A 3D Printed Fume Extractor”

Now we all know that CRTs draw one pixel at a time, drawing from left to right, top to bottom. You can capture this with a regular still camera at a high shutter speed. The light from a TV screen comes from a phosphor coating painted on the inside of the glass screen. Phosphor glows for some time after it is excited, but how long exactly? [Gavin and Dan’s] high framerate camera let them observe the phosphor staying illuminated for only about 6 lines before it started to fade away. You can see this effect at a relatively mundane 2500 FPS.

Now we all know that CRTs draw one pixel at a time, drawing from left to right, top to bottom. You can capture this with a regular still camera at a high shutter speed. The light from a TV screen comes from a phosphor coating painted on the inside of the glass screen. Phosphor glows for some time after it is excited, but how long exactly? [Gavin and Dan’s] high framerate camera let them observe the phosphor staying illuminated for only about 6 lines before it started to fade away. You can see this effect at a relatively mundane 2500 FPS.