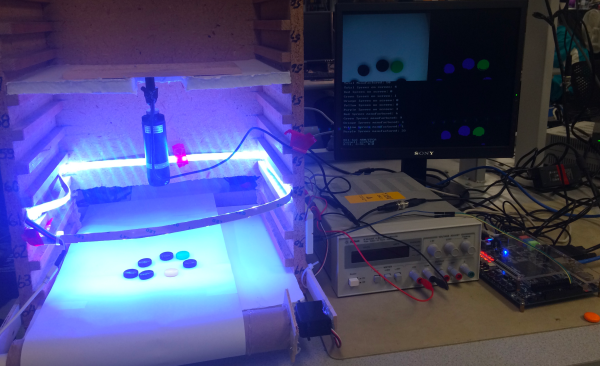

[Claire Chen] and [Mark Zhao], students in [Bruce Land]’s ECE5760 class at Cornell, created a project aimed at the manufacturing sector: quality-checking manufactured products automatically by visually scanning a bunch of them and processing the pixels one at a time. Ordinarily, the time when the widget comes off the line is when you have to bring in actual people to inspect. This project uses morphological image processing to like dilation and erosion to look for flaws.

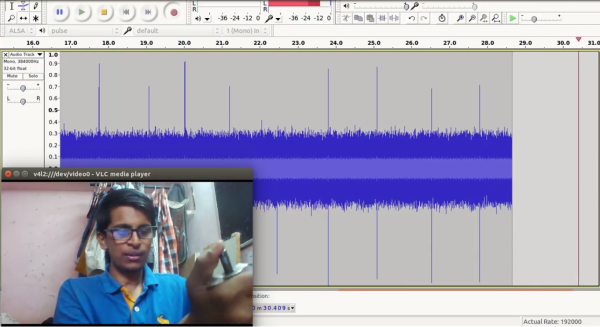

[Claire] and [Mark] created a simulated manufacturing line with a servo-driven belt that brings a series of Spree candies into the range of a camera, which scans them. The SoC with a Cyclone V FPGA and ARM Cortex-9 then processes the raw images to establish the object’s color, while running it through a couple of algorithms to look for defects. The FPGA tracks how many Sprees that have passed by as well as their color, maintaining a 99% success rate with a rate of 5-10 frames per second. The FPGA also looks at each blob of color as a collection of pixels, establishing connectivity to help to distinguish multiple Sprees touching each other.

Also be sure to check out [Claire] and [Mark]’s bike sonar project from a previous semester.

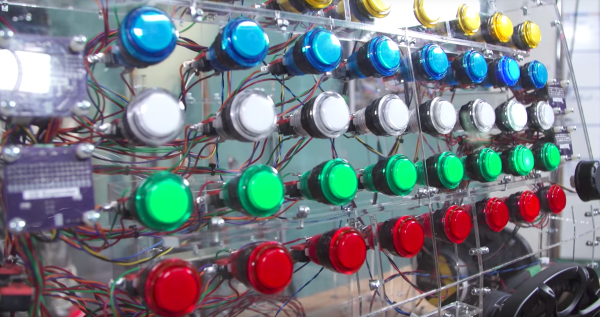

In order to control all of those buttons, the team designed

In order to control all of those buttons, the team designed