Parts, tools, and components for aviation and aerospace are sold in ‘Aviation Monetary Units’ (AMU). Right now, the conversion factor from USD to AMU is about 1000 to 1. This stuff is expensive, but there is a small portion of the flying community that prides itself on not breaking the bank every time something needs to be replaced. Theses are often the microlight, ultralight, and experimental aircraft enthusiasts. Steam gauges are becoming obsolete and expensive to repair, and you’re not going to throw a 15 AMU Garmin G500 in an ultralight that only costs 10 AMU.

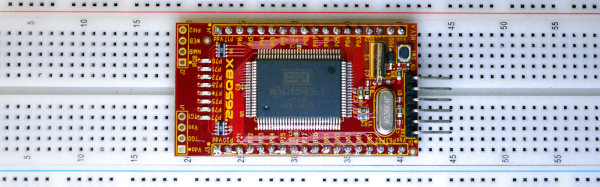

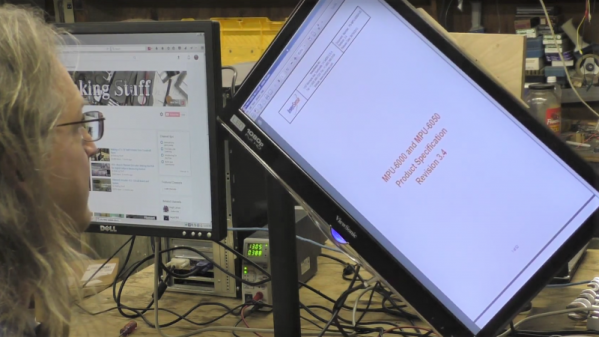

To solve this problem, [Rene] is turning to sensors, displays, and microcontrollers that are cheap and readily available to build modular aviation instruments.

As with all aviation gear, the first question that springs to mind is, ‘what will the FAA think about this?’. [Rene] is in South Africa, so the answer is, ‘nothing’. If a few American pilots decide to build one of these, that’ll fly too; these are instruments designed for non-type-certified aircraft. That’s not to say there are no rules for what goes into these aircraft, but the paperwork is much easier.

Right now, the design goals for [Rene]’s instruments is under 0.1 AMU per module, robust, RF shielded, with engine monitoring, fuel management, heading, air and ground speed, altitude, attitude, and all the other gauges that make flying easy. He’s using a CAN bus for all of these modules, and in the process slowly dragging the state of the art of ultralight aviation into the 1990s. It’s fantastic work, and we can’t wait to see some of these modules in the air.

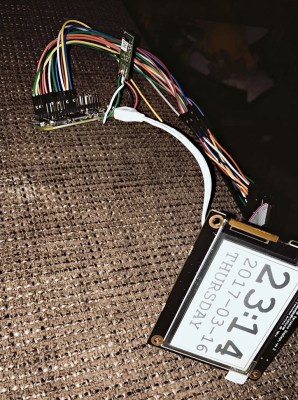

[Jannis Hermanns] couldn’t find a reason to control this outburst of nostalgia for the good old days of small, expensive computers and long hours spent clawing through the LEGO bin to find The Perfect Piece to finish a build. It turns out that the computer part of this replica was the easy part — it’s just an e-paper display driven by a Raspberry Pi Zero. Building the case was another matter, though.

[Jannis Hermanns] couldn’t find a reason to control this outburst of nostalgia for the good old days of small, expensive computers and long hours spent clawing through the LEGO bin to find The Perfect Piece to finish a build. It turns out that the computer part of this replica was the easy part — it’s just an e-paper display driven by a Raspberry Pi Zero. Building the case was another matter, though.