People argue about the first use of the computer desktop metaphor. Apple claims it. Xerox probably started it. Yet, when I think of computer desktops, I think of the NOVAL 760. Not a household name, to be sure, but a big ad spread in a June 1977 Byte magazine was proud to introduce it. At $2995, we doubt many were sold, but the selling point was… well… it was built into a “handsome wood desk, designed to compliment any decor.” The desk folded down when you were not using the computer, and the keyboard recessed into a drawer.

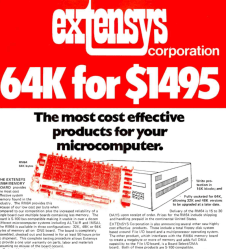

The computer itself was no slouch for 1977, but nothing you couldn’t find elsewhere. An 8080, speed unspecified, had 16 kB of RAM and 3 kB of PROM. There was also a display with a few kB of memory hanging around, too. And just in case you were worried, the bottom of the page entitled “The Ultimate in Home Computers” reads, “The NOVAL 760 COMPUTER. A fully-assembled, fully-tested personal computer … not a kit!” Of course, for us, that’s not really a selling point. If you wonder why the computer was memory limited, this is the time that Extensys bragged in an ad: 64 kB for $1495! If you ordered one, you could have it in 15 to 30 days, too!

The computer itself was no slouch for 1977, but nothing you couldn’t find elsewhere. An 8080, speed unspecified, had 16 kB of RAM and 3 kB of PROM. There was also a display with a few kB of memory hanging around, too. And just in case you were worried, the bottom of the page entitled “The Ultimate in Home Computers” reads, “The NOVAL 760 COMPUTER. A fully-assembled, fully-tested personal computer … not a kit!” Of course, for us, that’s not really a selling point. If you wonder why the computer was memory limited, this is the time that Extensys bragged in an ad: 64 kB for $1495! If you ordered one, you could have it in 15 to 30 days, too!

There were options for more memory, and it wasn’t clear how many of the I/O devices in the ad were actually included in the advertised price. Some of the devices seemed very specialized, so we are guessing the basic system didn’t include some of them.