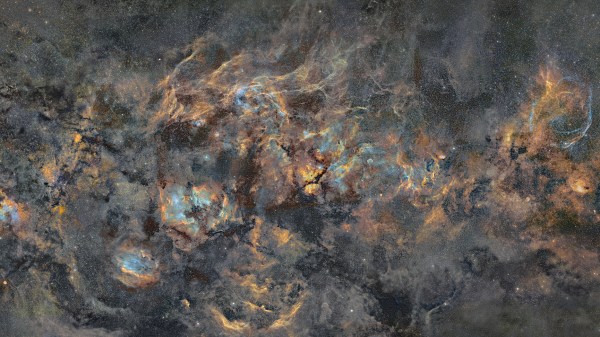

In the realm of amateur astronomy, enthusiasts find themselves navigating a cosmos in perpetual motion. Planets revolve around stars, which, in turn, orbit within galaxies. But the axial rotation of the Earth and the fact that its axis is tilted is the thing that tends to get in the way of viewing celestial bodies for any appreciable amount of time.

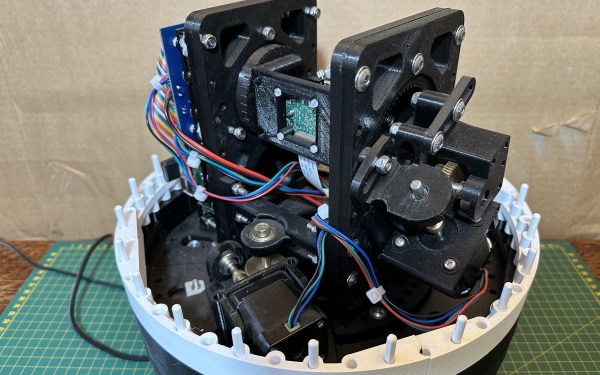

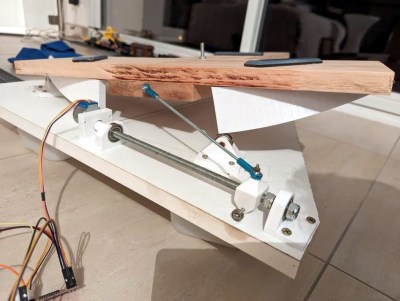

Amateur astronomy is filled with solutions to problems like these that don’t cost an arm and a leg, though, like this 3D printed equatorial table built by [aeropic]. An equatorial table is a device used to compensate for the Earth’s rotation, enabling telescopes to track celestial objects accurately. It aligns with the Earth’s axis, allowing the telescope to follow the apparent motion of stars and planets across the night sky.

Equatorial tables are specific to a location on the Earth, though, so [aeropic] designed this one to be usable for anyone between around 30° and 50° latitude. An OpenSCAD script generates the parts that are latitude-specific, which can then be 3D printed.

Equatorial tables are specific to a location on the Earth, though, so [aeropic] designed this one to be usable for anyone between around 30° and 50° latitude. An OpenSCAD script generates the parts that are latitude-specific, which can then be 3D printed.

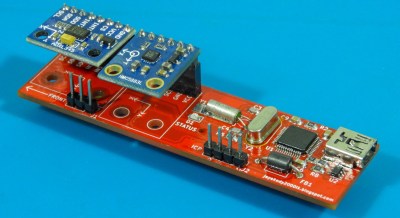

From there, the table is assembled, mounted on ball bearings, and powered by a small stepper motor controlled by an ESP32. The microcontroller allows a telescope, in this case a Newtonian SkyWatcher telescope, to track objects in the sky over long periods of time without any expensive commercially-available mounting systems.

Equatorial tables like these are indispensable for a number of reasons, such as long-exposure astrophotography, time lapse imaging, gathering a large amount of observational detail for scientific purposes, or simply as an educational tool to allow more viewing of objects in the sky and less fussing with the telescope. They’re also comparatively low-cost which is a major key in a hobby whose costs can get high quickly, but not even the telescope needs to be that expensive. A Dobsonian telescope can be put together fairly quickly sometimes using off-the-shelf parts from IKEA.