[Melka] wanted a track bike, but never quite got around to buying a nice one. Then he found an inexpensive abandoned project bike for 10 Euro. He had to do a lot of work to make it serviceable and he detailed it all in a forum post. What caught our eye, though, was his technique for electroetching.

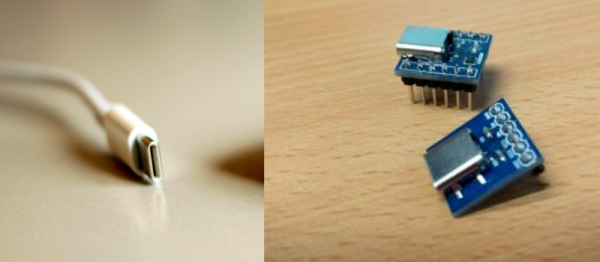

The process is simple, but [Melka] says the procedure caused hydrochloric acid fumes as a byproduct. Your lungs don’t like HCl fumes. Apart from the danger, you probably have everything you need. He used electrical tape to create a stencil on the metal (although he mentioned that Kapton tape might come off better afterward) and a saturated solution of common table salt as the electrolyte.

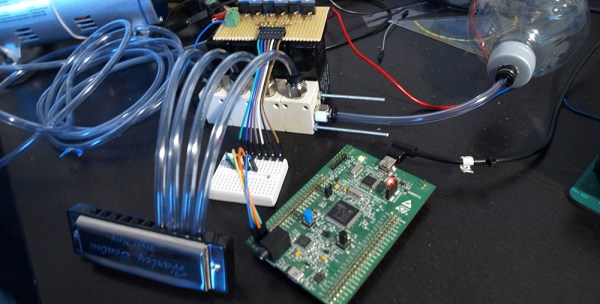

Power comes from a bench power supply set to about 24V. The positive lead was connected to the metal and the ground to the sponge. From the photos, it looks like the particular piece and solution caused about 600mA to flow. After 10 minutes, the metal etched out to about 0.2 mm. After the etching, [Melka] brazed some brass into the etched area to make an interesting looking logo.

If you have a laser cutter, you can skip the chemicals. We’ve even seen laser etching combine with a 3D printer to produce PCBs. [Melka’s] method is a little messier and probably would not do fine lines readily, but if you need to etch steel and you don’t mind the fumes, it should be simple to try.