[Paul] is very up-front about the realities of his $25 Satellite Tracker, which aims a tape measure yagi antenna at a satellite of choice and keeps it tracking the satellite as it moves overhead. Does it work? Yes! Is it cheap? Of course! Is it useful? Well… did we mention it works and it’s cheap?

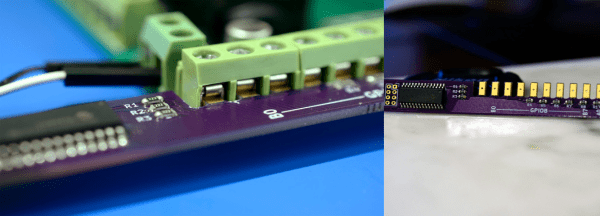

When [Paul] found himself wanting to see how cheaply he could make a satellite tracker he already had an RTL-SDR (which we have seen used for satellite communication before) and a yagi antenna made out of a tape measure, but wanted some way to automatically point the antenna at a satellite as it moved across the sky. He also wanted to see just how economically it could be done. Turns out that with some parts from China and code from SatNOGS (open-source satellite tracking network project and winner of the 2014 Hackaday Prize) you have most of what you need! A few modifications were still needed, and [Paul] describes them all in detail.

![]() So is a $25 Satellite Tracker useful? As [Paul] says, “Probably not.” He explains, “Most people want satellite trackers so that they can put them outside and then control the antenna from inside, which someone probably can’t do with mine unless they live in a really nice place or build a radome. […] Driving somewhere, setting it up correctly (which involves reprogramming the Arduino for every satellite), and then sitting around is pretty much the opposite of useful.”

So is a $25 Satellite Tracker useful? As [Paul] says, “Probably not.” He explains, “Most people want satellite trackers so that they can put them outside and then control the antenna from inside, which someone probably can’t do with mine unless they live in a really nice place or build a radome. […] Driving somewhere, setting it up correctly (which involves reprogramming the Arduino for every satellite), and then sitting around is pretty much the opposite of useful.”

It might not be the most practical but it works, it’s cool, he learned a lot, and he wrote up the entire process for others to learn from or duplicate. If that’s not useful, we don’t know what is.

Satellite tracking is the focus of some interesting projects. We’ve even seen a project that points out satellite positions by shining a laser into the sky.