Planning a hostile takeover of your local swimming pool? This might help: [Dr Anders Lyhne Christensen] sent us a note about his work at the BioMachines Lab of the Institute of Telecommunications in Portugal. They have been building a swarm of robot boats to experiment with autonomous swarms, with some excellent results.

In an autonomous swarm, each robot makes its own decisions and talks to its neighbors, and the combined behavior of the swarm produces an overall behavior, like ants in a nest. They’ve created swarms that can autonomously navigate, patrol an area or monitor the temperature in an area and return to base to report the results. In an excellent video, [Anders] outlines how they used computational evolution to create these behaviors, randomly mutating a neural net to find the best approach, which is then sent to the real boats.

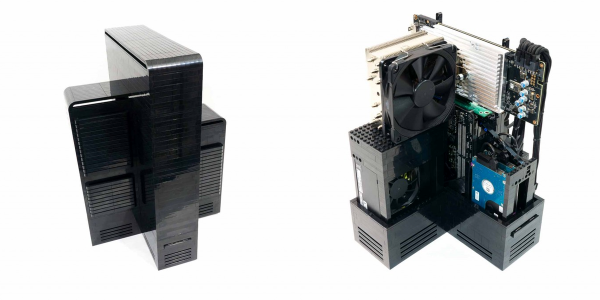

Perhaps coolest of all: the whole project is open source, with the brains of each boat running on a Raspberry Pi, and a CNC milled foam hull with 3D printed component mounts. Each boat costs about 300 Euro (about $340), but you could reduce the cost a bit by salvaging components and once the less-expensive Pi Zero becomes obtainable. This project will no doubt be useful for many an evil genius who is sick of being splashed by the toughs at the local pool: a swarm of killer robots surrounding them would be an excellent way to keep them at bay.

Continue reading “Swarm Of Robot Boats Coming To An Ocean Near You Soon”

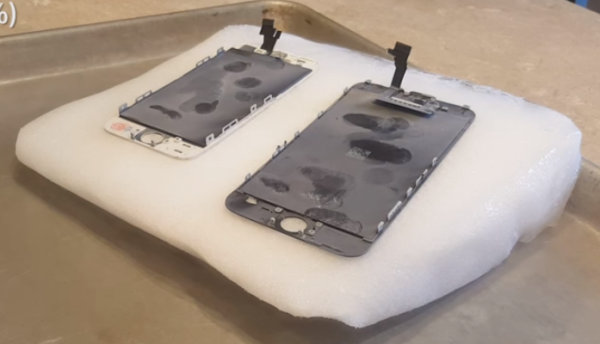

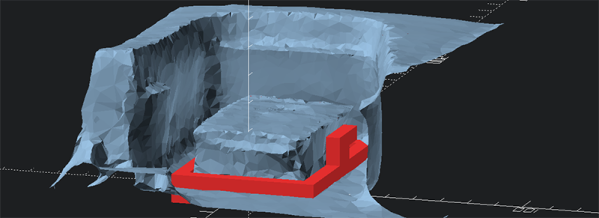

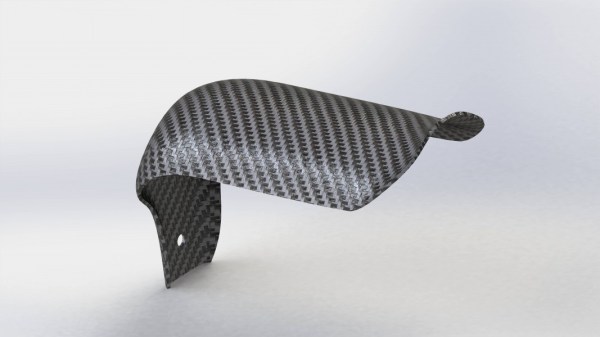

Photogrammetry requires taking a few dozen pictures with a camera, using software to turn these 2D images into a 3D model, and building the new part from that model. The software [Stefan] is using is

Photogrammetry requires taking a few dozen pictures with a camera, using software to turn these 2D images into a 3D model, and building the new part from that model. The software [Stefan] is using is

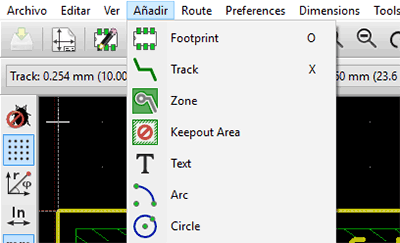

Mientras que ha habido otros intentos por localizar KiCad a otros idiomas, la mayoría de estos proyectos se encuentran incompletos. En una actualización de KiCad hace algunos meses, la localización al español ya contaba con algunas cadenas ya traducidas, pero no demasiadas. Los esfuerzos de [ElektroQuark] han acercado KiCad a millones de hablantes nativos de español, no solo algunos de sus menús.

Mientras que ha habido otros intentos por localizar KiCad a otros idiomas, la mayoría de estos proyectos se encuentran incompletos. En una actualización de KiCad hace algunos meses, la localización al español ya contaba con algunas cadenas ya traducidas, pero no demasiadas. Los esfuerzos de [ElektroQuark] han acercado KiCad a millones de hablantes nativos de español, no solo algunos de sus menús.