For a first try at an electric vehicle conversion we’re guessing that most would pick a small city car as a base vehicle, or perhaps a Kei van. Not [LiamTronix], who instead chose to do it with an old Ferguson tractor. It might not be the most promising of EV platforms, but as you can see in the video below, it results in a surprisingly practical agricultural vehicle.

A 1950s or 1960s tractor like the Ferguson usually has its engine as a structural member with the bellhousing taking the full strength of the machine and the front axle attached to the front of the block. Thus after he’s extracted the machine from its barn we see him parting engine and gearbox with plenty of support, as it’s a surprisingly hazardous process. These conversions rely upon making a precise plate to mount the motor perfectly in line with the input shaft. We see this process, plus that of making the splined coupler using the center of the old clutch plate. It’s been a while since we last did a clutch alignment, and seeing him using a 3D printed alignment tool we wish we’d had our printer back then.

The motor is surprisingly a DC unit, which he first tests with a 12 V car battery. We see the building of a hefty steel frame to take the place of the engine block in the structure, and then a battery pack that’s beautifully built. The final tractor at the end of the video still has a few additions before it’s finished, but it’s a usable machine we wouldn’t be ashamed to have for small round-the-farm tasks.

Surprisingly there haven’t been as many electric tractors on these pages as you’d expect, though we’ve seen some commercial ones.

Continue reading “An Electric Vehicle Conversion With A Difference”

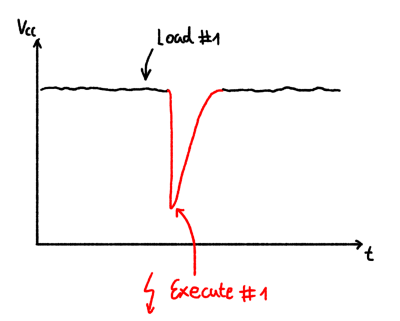

particular attack. If a programmed reset doesn’t get the job done, the target power is provided via a TPS2041 load switch to enable cold starts. The final part of the interface is an analog input provided by an SMA connector.

particular attack. If a programmed reset doesn’t get the job done, the target power is provided via a TPS2041 load switch to enable cold starts. The final part of the interface is an analog input provided by an SMA connector.