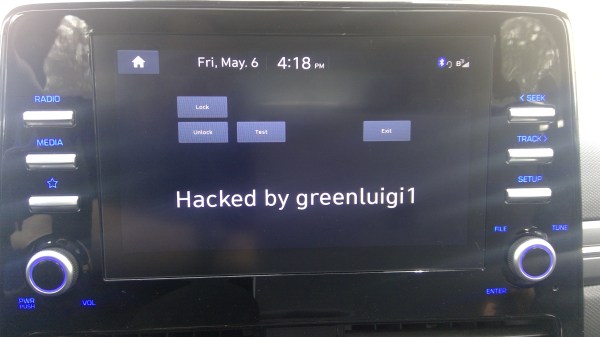

In the natural order of the world, porting DOOM to any newly unlocked computing system is an absolute given. This a rule which [greenluigi1] understands all too well, leading to presumably the first Hyundai to be equipped with this all-time classic on its infotainment system. This follows hot on the trail of re-hacking said infotainment system and a gaggle of basic apps being developed for and run on said head unit (being the part of the infotainment system on the front dashboard). Although it is a Linux-based system, this doesn’t mean that you can just recompile DOOM for it, mostly because of the rather proprietary system environment.

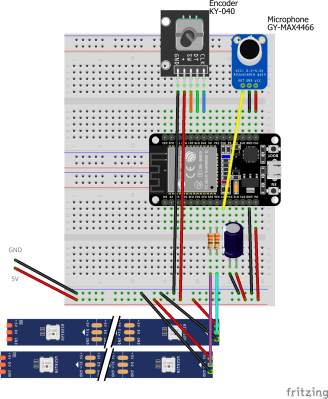

To make life easy, [greenluigi1] picked doomgeneric as the version to port. The main selling point of this project is that it only requires the developer to implement five functions to support a new platform, which then ‘just’ left figuring out how to do this on a head unit. Two of these (DG_SleepMs() and DG_GetTicksMS()) could be copied verbatim from the X11/xlib port, but the remaining three required a bit of sleuthing.

Where things go sideways is with keeping the head unit’s Helix window manager happy, and stick to the limited ways a GUI application can be launched, including the way arguments are passed. For the PoC, it was decided to just hardcode these arguments and only register the game with Helix using an .appconf configuration file. When it came to drawing pretty graphics on the screen, this was decidedly easier since the system uses Qt5 and thus offers the usual ways to draw to a QPixmap, which in this case maps to the framebuffer.

After a few playful sessions with the head unit’s watchdog timer, [greenluigi1] found himself staring at a blank screen, despite everything appearing to work. This turned out to be due to the alpha channel value of 0 that was being set by default, along with the need for an explicit refresh of the QPixmap. Up popped DOOM, which left just the implementation of the controls.

In order to start the game, you have to literally buckle up, and the steering wheel plus media control buttons are your inputs, which makes for a creative way to play, and perhaps wear some bald spots onto your tires if you’re not careful. If you’d like to give it a shot on your own ride, you can get the project files on GitHub.

Continue reading “Hyundai Is Doomed: Porting The 1993 Classic To A Hyundai Head Unit”