It’s hard to argue that Soviet-Era nuclear engineering may have some small flaws, what with the heavily-monitored exclusion zone around Chernobyl No.4. Evidently, their industrial designers were more on-the-ball, because [Alex] has crafted the absolute most stylish fallout monitor we’ve ever seen, with ESP32 and a vintage Soviet-designed plasma display to indicate radiation levels in the exclusion zone.

Since the device is not located within the zone, [Alex] is using the ESP32 to access sensor values published via an API at SaveEcoBot. He also includes a Geiger counter module for the background level at the current location. That’s straightforward enough– integrating the modern microcontroller with the vintage plasma display is where the real hacking comes in. Though they might not be as vintage as you think: apparently the Elektronika MS6205 remained in production until 2005, but 2005 is still vintage. [Alex] notes in the instructions on hackaday.io that we’re actually looking for a post-1995 model to follow along.

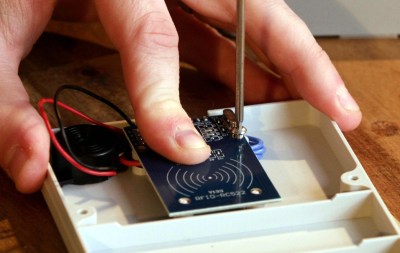

The Elektronika MS6205 is based on a 100×100 pixel plasma matrix, but it is operated as a text-only display with Latin and Cyrillic characters in ROM. The ROM also includes some extra symbols and Greek letters (the gamma will come in handy for this application) that can be unlocked by cutting a trace on the board and replacing it with a bodge wire. Igniting the display requires 250V, which will require more work for North Americans than it does in Ukraine. Driving the display requires interfacing with the 7-bit data bus and 8-bit address bus, but [Alex] has made the wiring and code available on the project site if you’re interested in these devices. If you want to watch it in action and get more background, check out the video embedded below.

These sorts of monochrome plasma displays have a lot of charm, and are absolutely worth reverse-engineering if you get your hands on different model. If you like the vibe of this display, you might also be interested in Vacuum Fluorescent Displays, which can be easier to find in the West.

Thanks to [Alex] for the tip. Like the tireless IEA workers at Chernobyl, we’re always monitoring the radiation level of our tips line. Continue reading “Vintage Plasma Display Shows Current Rad Levels”