Some people will do anything for a good cup of coffee, and we don’t blame them one bit — we’ve been known to pack up all our brewing equipment for road trips to avoid being stuck with whatever is waiting in the hotel room.

While this stylish lever-based industrial coffee machine made by [exthemius] doesn’t exactly make textbook espresso, it’s pretty darn close. Think of it like an Aeropress on steroids, or more appropriately, bulletproof coffee. As you can see in the demo after the break, the resulting coffee-spresso hybrid brew looks quite tasty.

While this stylish lever-based industrial coffee machine made by [exthemius] doesn’t exactly make textbook espresso, it’s pretty darn close. Think of it like an Aeropress on steroids, or more appropriately, bulletproof coffee. As you can see in the demo after the break, the resulting coffee-spresso hybrid brew looks quite tasty.

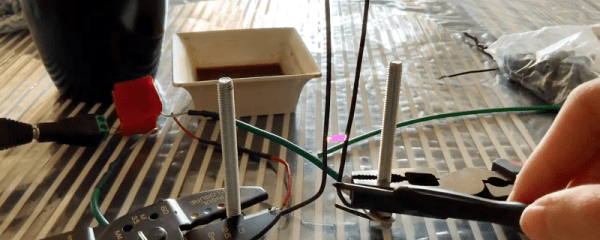

Here’s how it works: finely-ground beans go in a pressurized portafilter basket that was scavenged from an entry-level prosumer espresso machine. Pour boiling water into the top of the cylinder, and pull the giant lever down slowly to force it through the portafilter. Presto, you’re in thin, brown flavor town.

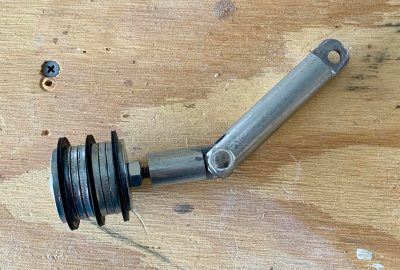

We love the piston-esque plunger that [exthemius] made by layering washers and rubber gaskets up like a tiramisu. Although there are no plans laid out, there’s probably enough info in the reddit thread to recreate it.

If you ever do find yourself stuck with hotel house brand, soak it overnight to make it much more palatable.

Continue reading “Impressive Lever-Press Espresso Machine Has Finesse”