A clock is perhaps one of the the most popular projects among makers. Most designs we see are purely electronic and do not bother with the often more complicated mechanical part. Instructables user [Looman_projects] though was not afraid of calculating gear ratios and tooth counts for his planetary gear clock.

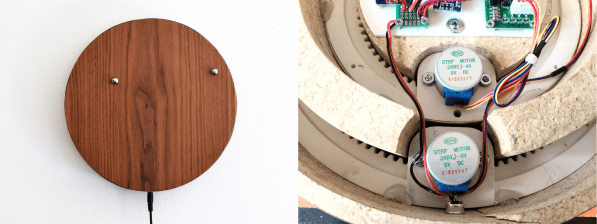

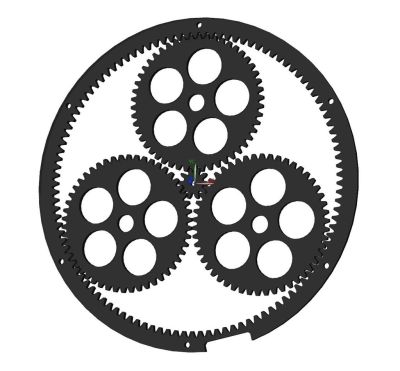

As shown in the picture, a planetary gear, also known as epicyclic gear, consists of three parts: a central sun gear, planetary gears moving around the sun gear and an outer ring with inward-facing teeth holding it all together. The mechanism dates back to ancient Greece but is still being used in car transmissions and has become quite popular in 3D printing. In his instructable [Looman_projects] has some useful inlinks including an explanation video of how planetary gear sets work and a website helping you to calculate the tooth counts for specific gear ratios. It is also noteworthy that he tried to cut the gears from aluminum with a waterjet which unfortunately failed because the parts were too small. What makes the clock visually stand out is the beautiful ornamental see-through design of the dial plate and hands made from laser-cut wood. Despite the mechanical gearbox, it is not surprising that the driving mechanism is based on ubiquitous pieces of digital electronics including an Arduino Nano, DS3231 RTC module, and a stepper motor. To avoid a cabling mess [Looman_projects] designed a custom PCB that interconnects all the electronics and says he even got some spare PCBs left for people interested in rebuilding the clock.

Actually, this is not the first laser-cut planetary gear clock that we have seen. In case you are wondering about the advantages of planetary gearboxes, you might want to check out how a 3D printed version is lifting an anvil.

Continue reading “Planetary Gears Tell Time In This Ornamental Clock”