Human ears are capable of perceiving frequencies from roughly 20 Hz up to 20 kHz, at least when new. Correspondingly, our audio hardware is designed more or less to target these frequencies. However, there’s often a little extra capability at the upper edges, which [Jacek] shows can be exploited to exfiltrate data.

The hack takes advantage of the fact that most computers can run their soundcards at a sample rate of up to 48 kHz, which thanks to the Nyquist theorem means they can output frequencies up to around 24 kHz — still outside the range of human hearing. Computers and laptops often use small speaker drivers too, which are able to readily generate sound at this frequency. Through the use of a simple Linux shell script, [Jacek] is able to have a laptop output Morse code over ultrasound, and pick it up with nothing more than a laptop’s internal microphone at up to 20 meters away.

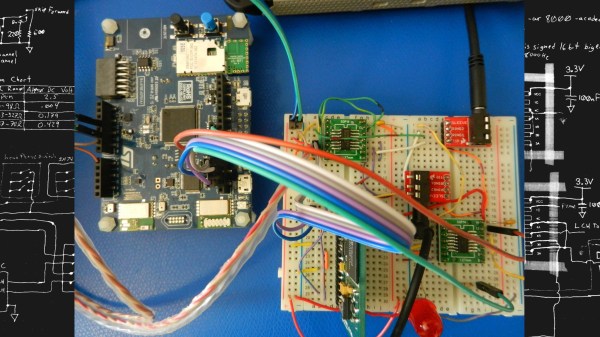

[Jacek] enjoys exploring alternative data exfiltration methods; he’s previously experimented with Ethernet leaks on the Raspberry Pi. Of course, with any airgap attack, the real challenge is often getting the remote machine to run the exfiltration script when there’s no existing remote admin access to be had. Video after the break.

That is the point of [Jake Ammons’] attention-getting lighthouse, designed and built in two weeks’ time for Architectural Robotics class. It detects ambient noise and responds to it by focusing light in the direction of the sound and changing the color of the light to a significant shade to indicate different events. Up inside the lighthouse is a Teensy 4.0 to read in the sound and spin a motor in response.

That is the point of [Jake Ammons’] attention-getting lighthouse, designed and built in two weeks’ time for Architectural Robotics class. It detects ambient noise and responds to it by focusing light in the direction of the sound and changing the color of the light to a significant shade to indicate different events. Up inside the lighthouse is a Teensy 4.0 to read in the sound and spin a motor in response.