How do you preserve high scores in an old arcade cabinet when disconnecting the power? Is it possible to inject new high scores into a pinball machine? It was the b-plot of an episode of Seinfield, so it has to be worth doing, leading [matthew venn] down the rabbit hole of FPGAs and memory maps to create new high scores in a pinball machine.

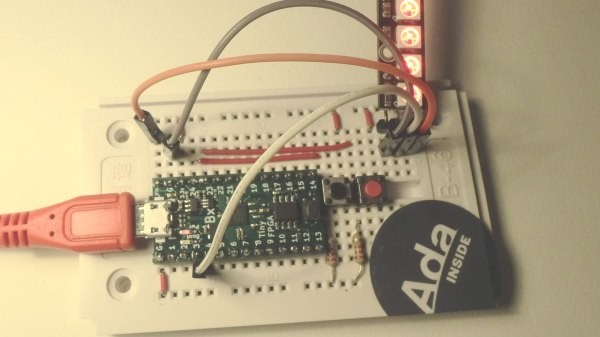

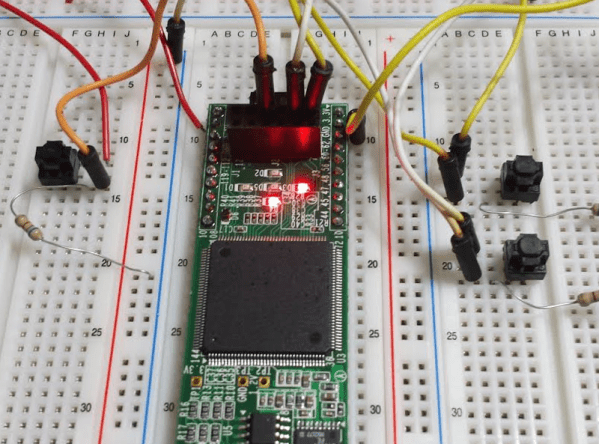

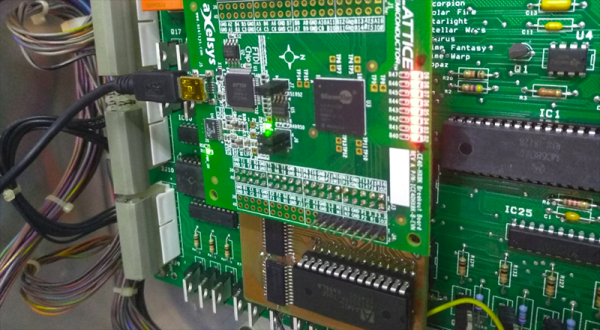

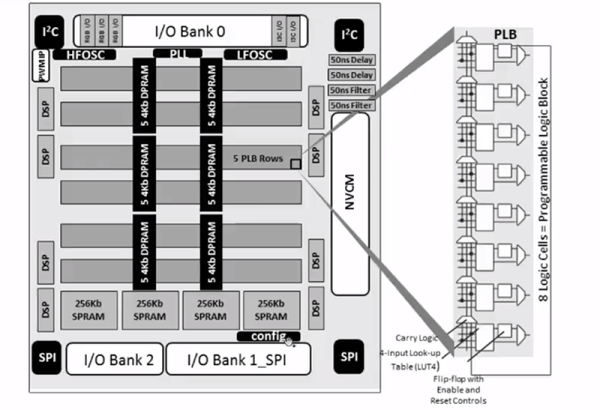

The machine in question for this experiment is Doctor Who from Williams, which, despite being a Doctor Who pinball machine isn’t that great of a machine. Still, daleks. This machine is powered by a Motorola 68B09E running at 2MHz, with 8kB of RAM at address 0x0000. This RAM backed up with a few AA batteries, and luckily is in a DIP socket, allowing [matthew] to fab a board loaded up with an FPGA development board that goes between the CPU and RAM.

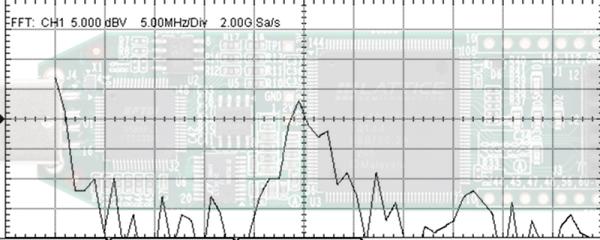

The basic technique for intercepting and writing a new high score for this pinball machine comes from the incredible [sprite_tm] who is tweeting high scores from a 1943 cabinet. The idea is simple: just have an FPGA look at one specific memory address, and send some data to a computer when the data at that address is updated. For the Doctor Who pinball machine, this is slightly harder than it sounds: the data isn’t stored in hex, but packed BCD. After a little bit of work, though, [matthew] was able to write new high scores from a Python script running on a laptop. All the code (and a few more details) are over on a Github

Extending arcade games by tapping into address and data lines isn’t something we see a lot of, but it has been done, most famously with the Church of Robotron. Here, a few MAME hacks turn a game of Robotron into a Church for the faithful to fully commit themselves to the savior of the world, due to arrive in 66 years and save the remaining humans from the robot apocalypse. This hack of a Doctor Who pinball machine goes beyond a modded version of MAME, and if we’re ever going to make a real chapel with a real game of Robotron, these are the techniques we’re going to use.